These lines are taken from a 1942 speech by Britain’s then Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, but they seem an oddly appropriate description of the current state of the war on Covid. The global response to the pandemic has been very variable, with developed nations spending more aggressively whilst poorer countries have been held back, by budgetary constraints, from carrying out mass vaccination to the same extent.

It is now becoming clear that new variants of the virus will continue to emerge, but unlike SARS this virus seems intent on plaguing us for the foreseeable future. What does this mean for economies and financial markets?

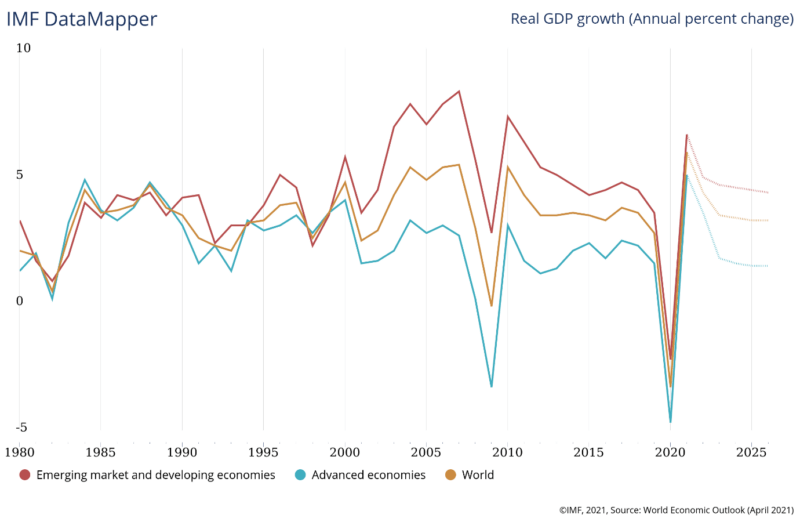

Before attempting to answer this question it is worth looking back at the economic collapse and rebound in the wake of the disease. The chart below shows the path of World GDP, together with the performance of emerging and developing economies, and advanced economies. The economic contraction was the largest since the Depression of the 1930s – the subsequent rebound has been simply unprecedented: –

The price of risk assets, for which global equities are a reasonable proxy, have followed a similar trajectory. Below is the MSCI World Index since 1993: –

Of course, the spectacular rebound in equity prices has been driven, at least in part, by a massive increase in fiscal spending by governments, combined with a reduction of interest rates and the implementation of even more aggressive asset purchase programmes by their beneficent central banks. Now that economies are beginning to reopen, however, fiscal spending is likely to moderate. Also, the spectre of consumer price inflation has reared its ugly head for the first time in a generation, prompting markets to ponder the prospect of central bank tapering of quantitative easing. Should this tapering prove insufficient to dampen the animal spirits of economic resurgence, there is even the prospect of an actual tightening of US monetary policy in the offing.

The release of the minutes of the July 27-28 Federal Open Market Committee meeting suggest that the Federal Reserve (Fed) will start to reduce the quantum of its asset purchase programme in the autumn. However, federal fund futures contracts imply that short-term interest rates will remain near the zero bound until the autumn of 2022, rising to the giddy heights of 50 basis points by mid-2023. Despite pressing to new highs this week equity (and bond) markets remain nervous.

Even the recent gentle change in the emphasis of Fed forward guidance has come as a surprise to some observers, since the official line for most of 2021 has been that any uptick in inflation is likely to be transitory. The sources of this new bout of inflation have many origins, some of which may prove more structural in nature than the Fed would care to admit. Aside from the expansion of money supply – which is the effective debasement of our fiat currencies most of us have known for the majority of our working lives – economies are faced with the prospect of adjusting to both a supply and demand-side shock on a scale not seen in most of our lifetimes.

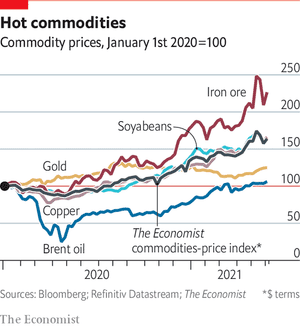

With the arrival of Covid-19, spending on services collapsed as many sectors of the economy were forced to shut down. Consumer demand switched from services to goods, putting pressure on already creaking global supply chains. Demand for products, such as lumber for home improvements (and even chairs for home offices) became severely supply-constrained. Bottlenecks have appeared across multiple industries. In many instances, such as the global shortage of microchips, these constraints remain even as consumer demand has started to swing back towards services. The chart below shows the increases in the prices of some of key commodities: –

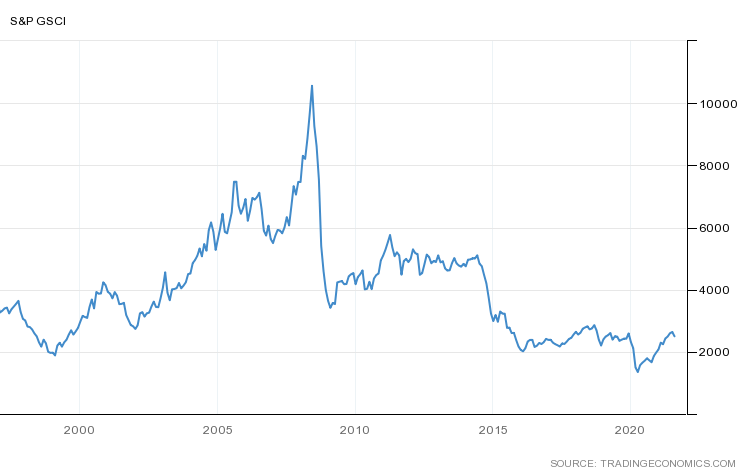

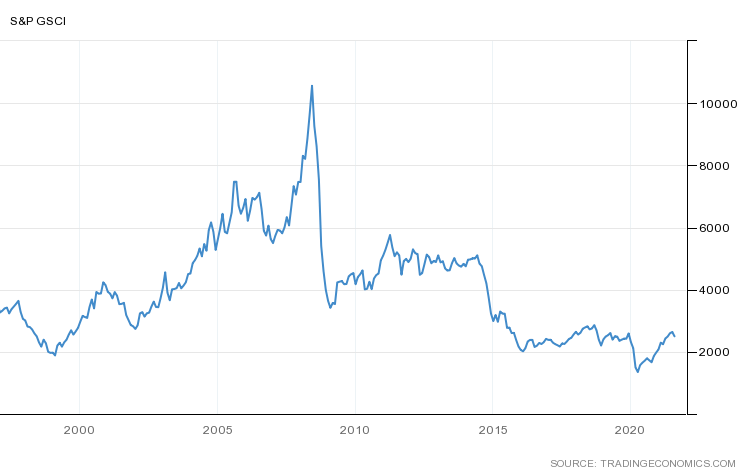

Commodity prices may have risen rapidly but they are rising from a low long-term base, as the next chart reveals; this poses a challenge to the transitory rhetoric to which central bankers have clung, with almost religious zeal, thus far: –

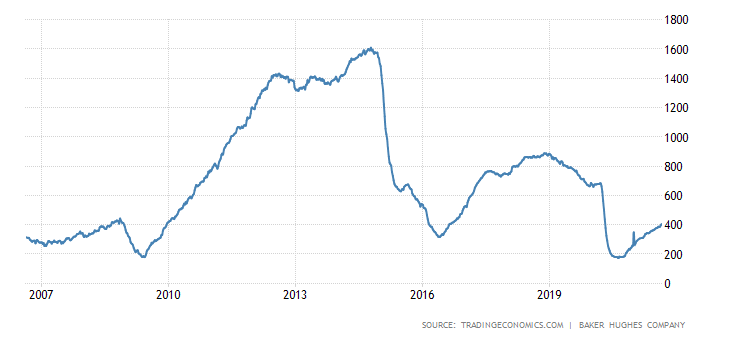

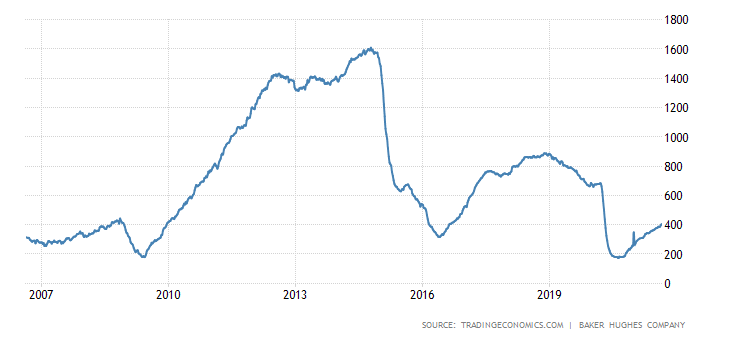

It is unwise to generalise about commodity markets, as they are incredibly diverse and the GSCI Index (shown in the chart above) has a 54% weighting to energy. However, with geopolitical risk in the ascendant (Afghanistan, China, Taiwan etc.) it is unlikely that oil prices will stage a collapse as they did in the initial aftermath of the pandemic. Higher oil prices will see the US oil rig count rise in response, but as you can see from the chart below, new wells still take time to come on stream even with the improvements of drilling technology seen over the past decade: –

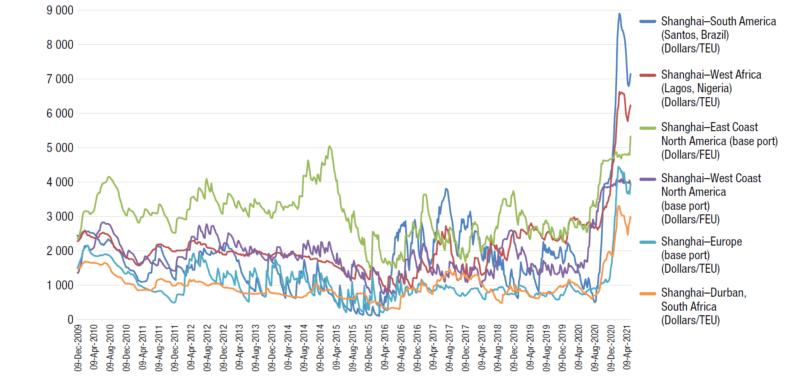

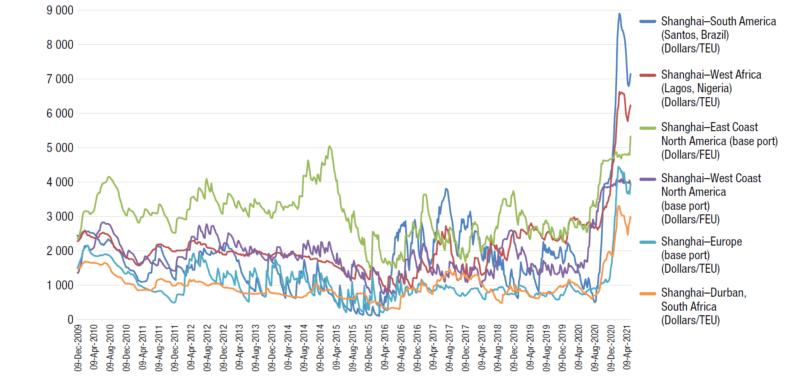

Oil prices may have moderated somewhat of late, but freight rates remain elevated as logistics networks struggle to respond to the dramatic changes in consumer demand: –

Without an easing of supply-chain constraints, scarcity of product will drive prices higher, regardless of global manufacturing capacity. A recent McKinsey video highlights some of the issues; sustained household demand for goods driven by increased savings; subdued demand for services, especially transportation; reduction in freight capacity and the long lead time required to deliver new vessels – whilst production methods are more efficient than in the past, as a container ship still takes around 18 months to complete. These factors will dominate well into 2022.

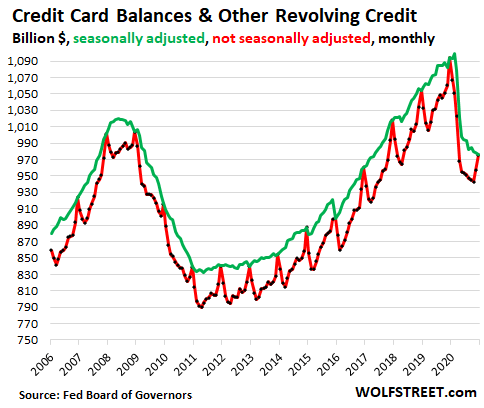

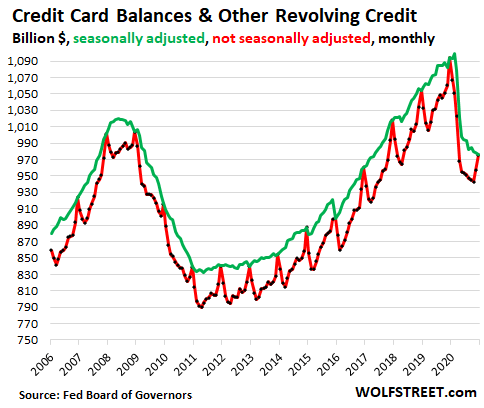

Another factor driving inflation has been the generosity of government furlough schemes. These programmes have seen many workers paid more to remain at home than they previously received from employment. Whilst the schemes remain in place, staff shortages, especially in sectors such as hospitality, will underpin the rising trend in wage settlements. Of course, once the furlough schemes end, workers will return to fill vacancies, but during the pandemic household savings has also risen dramatically. Some of the most expensive types of debt have been reduced. Financial pressure on the previously employed to rapidly return to the workforce remains subdued. The chart below shows credit card and other revolving credit to Q4 2020 : –

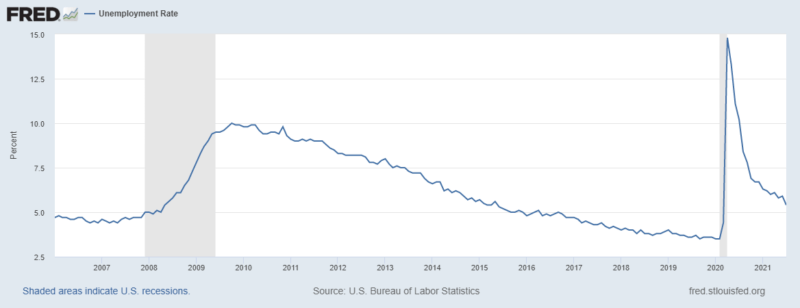

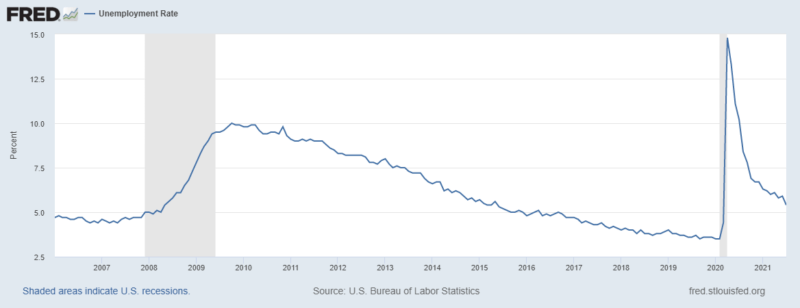

Those who still expect the current inflationary phase to be transitory focus on US unemployment. Although the rate has fallen from the double-digit levels of the initial outbreak – it rose from 3.5% in February 2020 to a high of 14.8% in April of that year – at 5.4% it remains 50% above its pre-Covid level: –

The inflationists, meanwhile, point to the elevated level of Job Vacancies. At more than 10 million, they are not only at their highest level since records began in 2001, but up 40% from the 7 million openings advertised on the eve of the lockdown: –

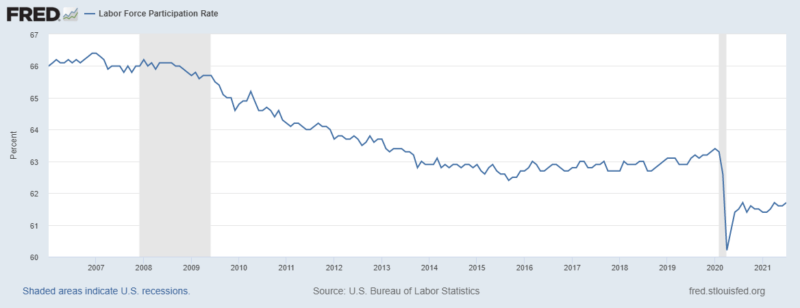

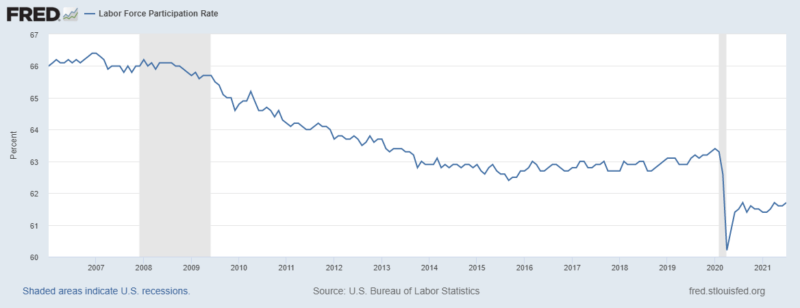

The shortage of workers is partly a result of government welfare programmes but a more structural factor is at play – an acceleration in the downward trend of labour force participation: –

Structural change

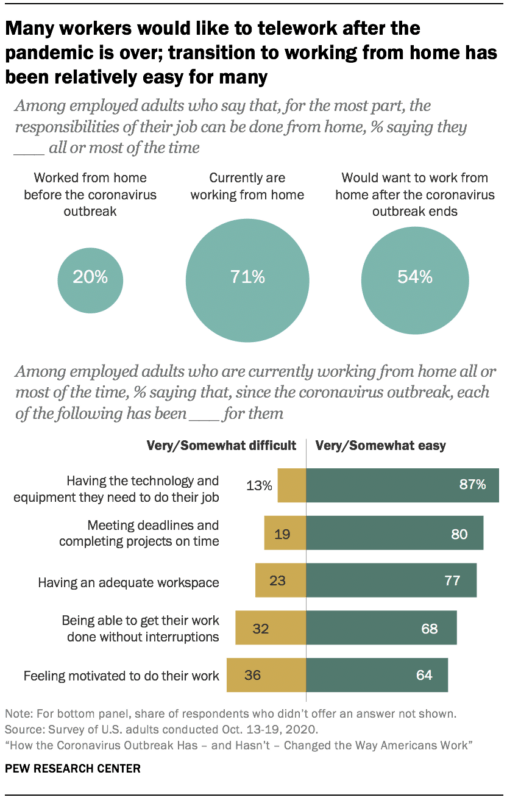

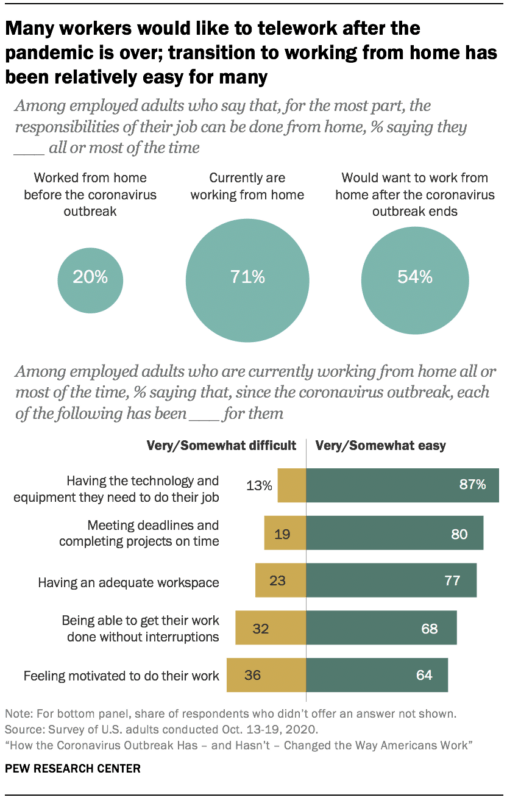

The pandemic has accelerated many economic trends, not just the decline in the participation rate. Some of these trends may now reverse, but the world of work has changed forever. According to a Pew Research study from December 2020, prior to the crisis, of those who could work from home, only 20% did. After the outbreak this rose to 71%. More importantly, 54% now wish to continue: –

Similar patterns have been evident in other developed countries; however, a doubling or tripling of the numbers working from home has had profound effects. These have included a reduction in demand for commercial office space and a concomitant increase in the price of larger and more geographically dispersed residences, together with the associated increased demand for home working services such as broadband, laptops, printers and office furniture. Demand for builders of extensions and loft conversions has never been stronger.

For many global corporations the zenith of their global supply-chain infrastructure was undermined by the great financial crisis; robustness rather than efficiency was already the objective prior to the viral outbreak. The US-China trade war has lent impetus to corporate initiatives to establish relationships with multiple suppliers of raw materials, semi-manufactured, manufactured and even finished products. Robustness is expensive; its cost must be swallowed by corporations or passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

The aftermath of Lockdown will not prove entirely negative for the global economy; whilst supply-chain costs have increased and product shortages will be with us for some time, the advances in technology, fuelled in part by plentiful venture capital and near zero interest rates, will bring lasting benefit for the consumer and wider economy. Measuring these productivity enhancements will, as always, prove challenging, especially in the services sector. The next decade may prove disappointing for public equity market investors, as earnings growth is likely to disappoint given the high plateau upon which it already stands. However, the seeds of new industries have been sewn in a rapid and concentrated manner. The entire world has been in a state akin to a war footing; one of the only positive side-effects of wars is the windfall of technological advancement.

It is difficult to imagine inflation of the type seen in the 1970s and 1980s taking root again unless fiscal policy runs wild and central bank attempts to reign in inflationary excess are overruled by their elected governments. However, risks remain and the prospects for the global economy After Lockdown remain uncertain. Much of the private wealth accumulated over the past few decades will probably be socialised in order to recompense the public purse. Taxes are likely to rise and debt will be rescheduled, but the alternatives to higher taxes or debt jubilees is even less palatable.

Government bond yields are likely to remain below inflation for the foreseeable future, pushing investors begrudgingly into otherwise expensive stocks. Fiat currencies will continue their race to the bottom and commodities, coming from a low base, should provide some protection from the ravages of inflation and debasement. Honest valuation remains difficult when markets are so hampered. The next decade is likely to favour the tactical investor.