Negotiations over President Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan rage on. The budget bill, which initially included $3.5 trillion in expenditures over 10 years, will likely be scaled back to $2 trillion. But some key senators, including Joe Manchin (D-WV), have said even this costs too much. The administration, in contrast, maintains that the proposed budget “costs zero dollars.”

The claim that a $3.5 or $2 trillion budget is actually costless strikes most people as crazy. Just look at the price tag, they say. But the administration does not deny the price of the proposed expenditures. Rather, it invokes the old idea that deficit spending pays for itself. In this view, deficit spending is an input that yields higher levels of economic productivity, which more than covers the cost of the expenditures. Budget deficits, in other words, are a profitable investment––generating a net benefit, not a net cost.

Do fiscal deficits actually improve the rate of economic growth? Economist Robert Barro raised this question in a famous 1974 paper, renewing interest in so-called Ricardian equivalence.

Ricardian equivalence starts with the idea that taxpayers are forward looking. An increase in government spending due to growing deficits necessarily implies future taxes. When deficits increase, forward-looking taxpayers will reduce private expenditures. Under perfect Ricardian equivalence, a marginal increase in the deficit is offset exactly by a reduction in private expenditure.

One way to think about Ricardian equivalence is in terms of crowding out. The spending of forward-looking agents is crowded out by deficit spending that entails future taxation. Under the current monetary-fiscal arrangement, we are experiencing crowding out of a different kind.

At the time Barro wrote his article, the Federal Reserve’s accumulation of U.S. Treasuries would generate inflation if the rate of accumulation was too great. Higher inflation translates to higher interest rates, thus limiting the ability of the central bank to reduce the cost of borrowing for the state. Under the current regime of unconventional monetary policy, inflationary pressure is muted by the Fed’s crediting of banks’ deposit accounts held at the Fed. Newly created money that never circulates in the financial system does not cause inflation. We are yet to find the upper limit of support for the U.S. Treasury by the Federal Reserve.

The Federal Reserve is able to expand its assets greatly in excess of the quantity of currency in circulation. This allows the central bank to support fiscal expansion without generating inflation. It also has the effect of allocating credit to the U.S. Treasury or whichever borrower is favored by monetary policy. What has gone unnoticed, however, has been the impact of growing deficits on private investment. In what follows we will investigate this relationship by reviewing data reflecting public investment, private investment, and economic productivity.

Credit Allocation Reduces Private Investment

For more than a decade, the Federal Reserve has engaged in credit allocation that blurs the line between monetary and fiscal policy. Monetary policy is thought to be accommodative when the Federal Reserve expands its balance sheet in excess of currency in circulation. The greatest portion of this expansion includes the purchase of U.S. Treasuries by the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve has tended to suppress the value of the federal funds rate; it has been near zero for most years since the financial crisis in 2008. It so happens that the changes in the federal funds rate have tended to outpace changes in the rate on AAA-rated corporate debt. So an artificially low federal funds rate has tended to increase the gap between these rates.

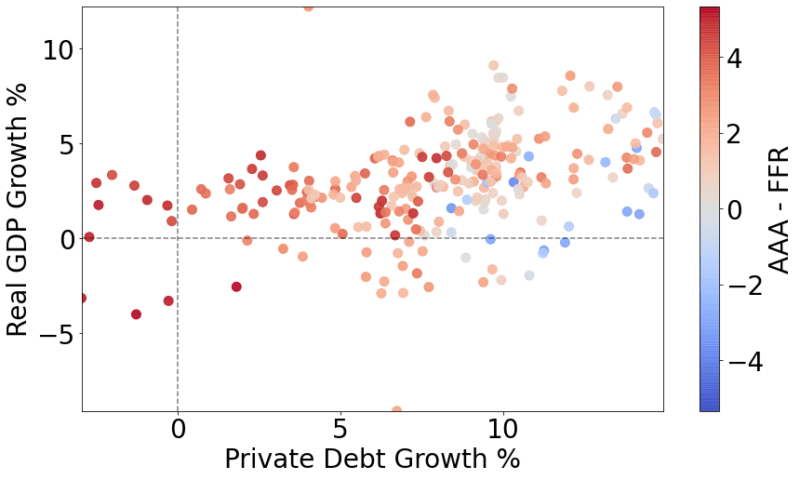

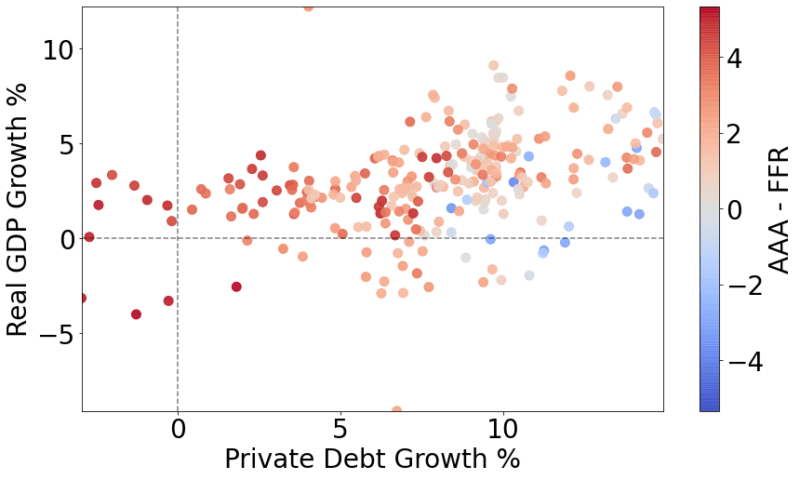

One must ask: why has a relatively higher rate of return for lending to private companies not yielded a greater level of private investment? One might argue that the effect of deficit spending on nominal GDP has at worst a neutral effect. Yet, it is a growing private debt ––i.e., growing private investment––not a growing public debt that is strongly associated with economic growth. If financial resources are being allocated toward the activities of the federal government, they are being allocated away from private economic activity. The supply of savings made available to private borrowers has fallen and the rates on private debt are relatively higher than the federal funds rate in consequence. A growing spread between the rate paid on AAA-rated corporate debt and the federal funds rate, meaning that public borrowing becomes relatively cheaper, is strongly correlated with a lower growth rate of GDP and a relatively larger level of public (smaller level of private) debt.