The expression “not worth a Continental,” meaning “not worth a Continental Dollar,” came into the lexicon during the Revolutionary War, when recourse to paper money drove up prices, ruined the economy, and nearly caused us to lose the war.

In 1775, practically at the outset of hostilities, the Continental Congress authorized an issue of $2 million in paper money. By the end of 1776, $25 million was in circulation, already at a 30 percent discount relative to silver. By the end of 1777, $38 million was in circulation, at a 70 percent discount relative to silver. By the end of 1779, $192 million was in circulation, and $1 in paper money was worth only 1 or 2¢ in silver. The states were issuing their own paper money, contributing to the inflation.

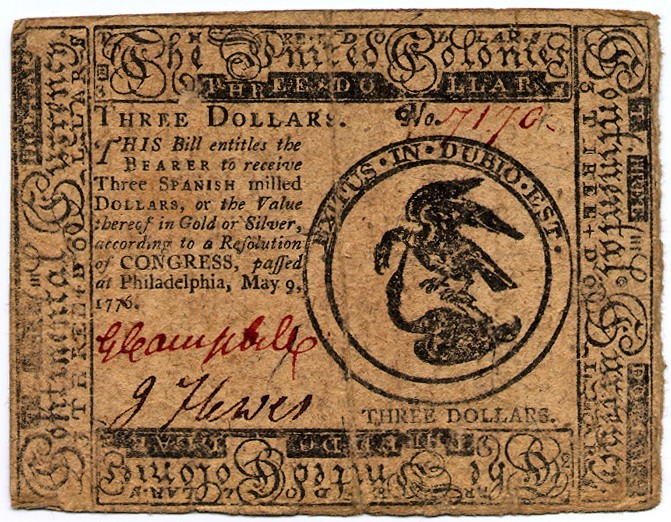

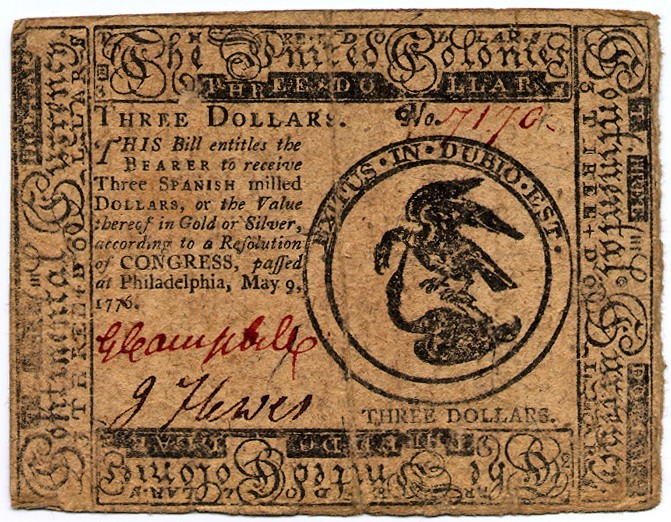

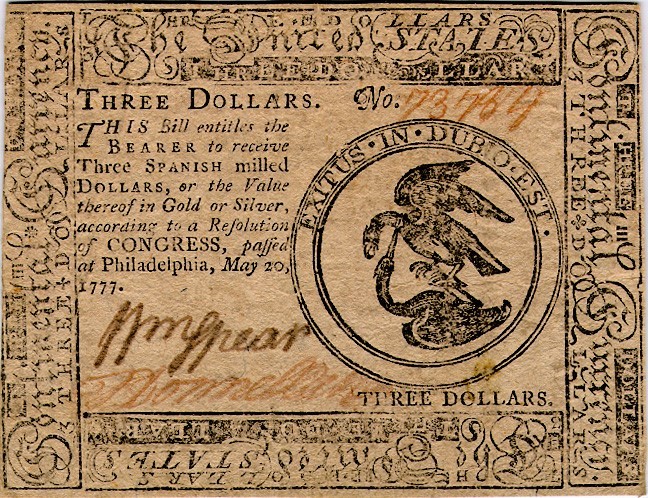

Figure 1. A Three Dollar note issued by the Continental Congress prior to the Declaration of Independence. (notice the inscription “United Colonies”)

Collections of the Hesburgh Libraries of Notre Dame.

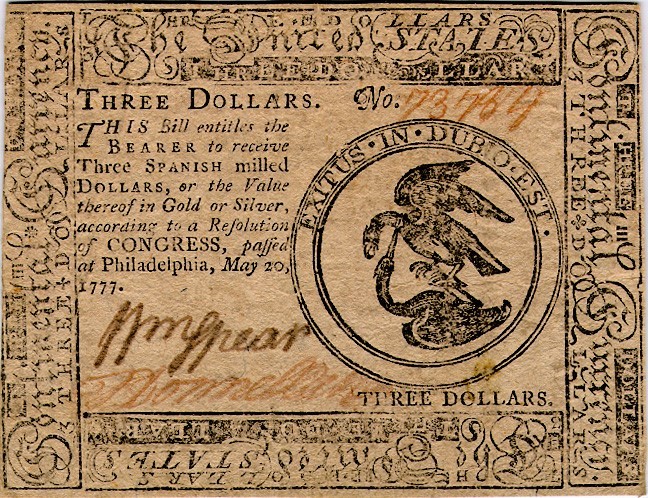

Figure 2. A Three Dollar note issued by the Continental Congress after the Declaration of Independence. (notice the inscription “United States”)

Collections of the Hesburgh Libraries of Notre Dame.

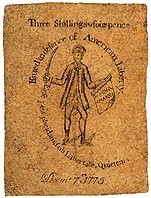

Figure 3. A Three Shilling “Sword in Hand” note issued by Massachusetts before the Declaration of Independence. (notice the patriot is holding Magna Carta)

Collections of the Hesburgh Libraries of Notre Dame.

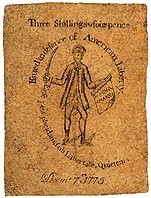

Figure 4. A Forty-eight Shilling “Sword in Hand” note issued by Massachusetts after the Declaration of Independence. (notice the patriot is holding the Declaration)

Collections of the Hesburgh Libraries of Notre Dame.

With so much paper money, prices were skyrocketing, and specie was being hoarded. At one point, George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, remarked that a wagon load of money would not buy a wagon load of provisions. Innkeepers, merchants and farmers were refusing to do business in terms of money. In October 1779, the Continental Congress requested not money from the states, but actual supplies – such as corn, wheat, hay and oats – in order to support the armies in the field.

In Massachusetts and the other states, attempts were made to fix maximum prices and to compel supply, with severe penalties against “forestalling,” “monopoly,” “oppression,” “extortion” and the like. In January 1777, Massachusetts passed a law covering the prices of 50 articles, such as “good Indian meal or corn” 4 shillings a bushel, and “good well-fatted grass-fed beef,” 3 pence a pound. But the act did not last long, and in May 1777 another was passed, which also did not last long. A total of eight conferences were held among the New England states to coordinate the control of prices, each one of which failed.

Among those hurting from the rapidly rising prices were soldiers and their families. The first attempt to ameliorate their condition was a law requiring sale to them at legal prices, which was a sham. In 1779, the soldiers of four Massachusetts battalions petitioned the state for relief, complaining that they were losing seven-eighths of their pay to depreciation. The state responded with a similar useless law requiring sale to them at legal prices, and a declaration that the state would make good on their wages at the end of the war.

Many of these soldiers had joined for three years under resolutions of the Continental Congress and of the state of Massachusetts in late 1776, and so their terms of service were about to expire. The south and parts of the north were controlled by the British, and the alliance with France had yet to yield material support. The Continental Congress and the state legislature were extremely anxious concerning the army.

In early 1780, Massachusetts passed a bill to pay its soldiers according to the average price of four items: beef, corn, wool and leather. This may have been the second instance of a price index clause in the world’s history (Massachusetts having invented the price index clause to deal with inflation during King George’s War); and the first time that a price index clause was actually implemented. Not only was this price index used to adjust soldiers’ pay, it was used in at least a few other cases to adjust other monetary amounts so as to reflect the value of paper money.

Financially, even more than militarily, 1780 was the most crucial year of the war. In May, King George III said that the financial distress in America would force the revolutionaries to sue for peace. He was not alone in that opinion. At about the same time, Washington wrote, “We seem to be verging so fast to extinction that I am filled with sensations to which I have been a stranger till these three months.” Alexander Hamilton said that France must be told that without a loan America would have to make terms with Great Britain. A French envoy secretly offered the British a truce involving their retaining New York, Georgia and the Carolinas, but it was rejected.

The Continental Congress sent envoys to France to beg for aid, in military forces, in supplies, and in silver. The French government, itself heavily burdened by war expenses, provided funds for the purchase in Europe of desperately needed supplies, for the payment of interest on American debt placed with European creditors, and a relatively small but critical amount of silver for transport to the colonies.

Thereupon, and under the direction of its new treasurer, Robert Morris, the Continental Congress essentially repudiated its paper money. The outstanding amount was to be redeemed through payment of taxes to the states, and exchanged at the rate of $40 in paper money to $1 in silver. Through this expedient, $120 million of paper money was retired. Another $6 million was exchanged for bonds, at the rate of $1 in paper money to 1¢ in silver, and the balance was presumed lost, destroyed or retained as souvenirs.

State-issued paper money, in the aggregate about $250 million, was handled on a state-by-state basis. In the worst cases, Georgia and Virginia, it was accepted in payment of taxes at the rate of $1,000 in paper money for $1 in silver. (In these two states and North Carolina, the Continental Dollar continued to circulate for about a year following its collapse elsewhere, during which time these states suffered a continuing depreciation of their currency.) New York was more representative, accepting its paper money in payment of taxes at the rate of $128 in paper money for $1 in silver. In Pennsylvania, the state accepted its paper money at the rate of $175 to $1.

Almost immediately, monetary reform revived commerce, both domestic and foreign. Silver flowed where it was formerly unavailable, coming out of hoards, as well as from the expenditures of both the British and French armies. The new paper money, e.g., issued by the (private) Bank of North America exchanged for silver at par. A French army joined with our army, and its commander, General Rochambeau, graciously put himself and his force under the authority of Washington. Together, they pinned a British army under General Cornwallis against the sea at Yorktown, Virginia, and won the battle that turned the world upside down.

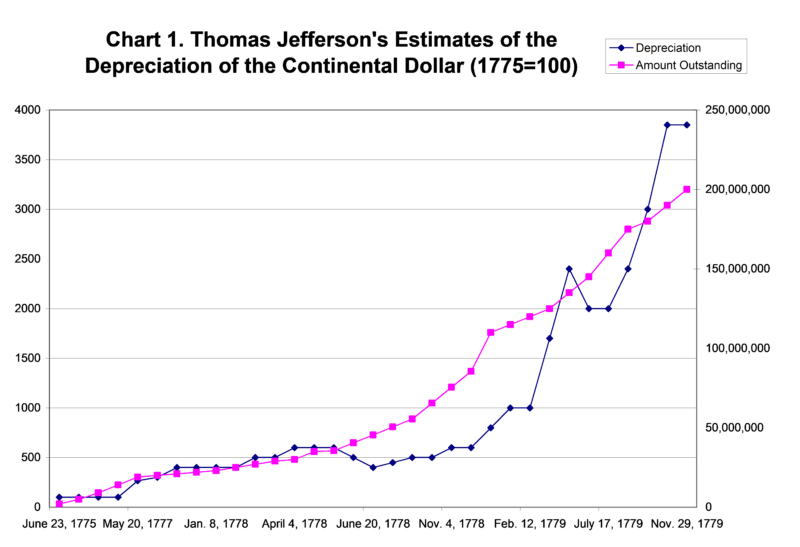

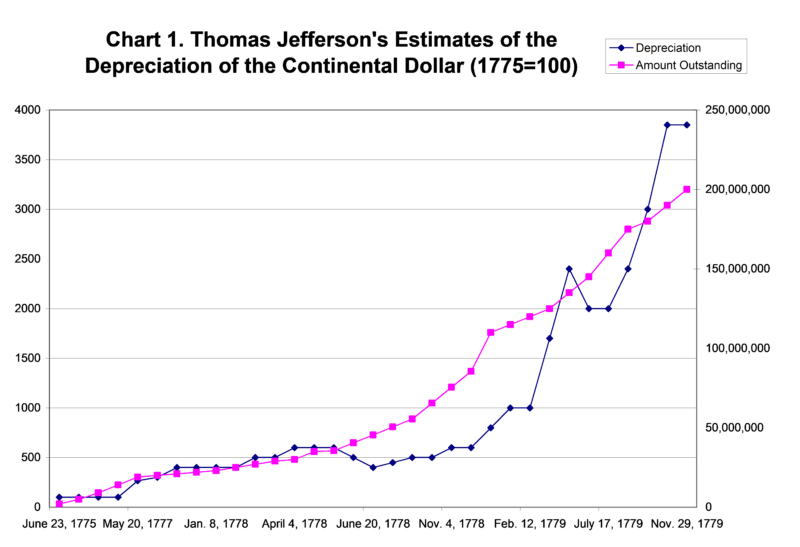

In hindsight, it is difficult to fathom how the patriots erred so grievously in issuing paper money during the Revolution. At least a certain amount of them were aware that only a limited amount of paper money could be issued before engendering an inflationary spiral. Pelatiah Webster, a particularly astute observer of the monetary affairs of the time, estimated that, in 1776, the “demand for money” in the states totaled about $30 million, of which about $12 million was “supplied” by specie and the remainder by various forms of colonial paper money. A limited amount of Continental Dollars could, therefore, be issued, displacing the specie in circulation and possibly also the colonial paper money then in circulation, before depreciation would set in. Following the war, the money thus issued could be withdrawn from circulation through taxation, and destroyed. Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, among others, reasoned similarly. Jefferson, a keen observer, kept track of the amount outstanding of the Continental Dollar, and of its depreciation. See Chart 1. His figures compare well with those of a Philadelphia broker. See Chart 2.