In the early days of the COVID pandemic, the Federal Reserve and central banks around the world pulled out all the stops. Policy rates were yanked to Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) levels, facilities were extended to provide liquidity to firms having difficulty selling securities in the primary and secondary markets, and direct lending to individuals and firms reached never-before-seen levels. Programs targeting niche markets, such as the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (originally introduced during the 2008 crisis), were reopened. And the Fed’s discount window, at which depository institutions can pledge bundles of loans, investment-grade securities, and other collateral for emergency funding, saw its use spike upward, rivaling the darkest days of 2008.

Because of its nature (the discount window is usually marketed as a relief valve for stressed financial institutions, which may presage financial stability problems) there is a stigma associated with its use. This is not entirely justified, as there are certainly firms that make use of the discount window periodically without liquidity problems. A prime example of those are small banks that face considerable and/or unpredictable seasonal business fluctuations.

The use of the Fed’s discount window tends to be viewed as a source of concern among other banking firms, caveats notwithstanding. A measure taken to facilitate the use of the discount window without the effect of freezing the borrowing institution out of other lending markets is the introduction of a two-year gap between use of the window and the Fed’s public release of the names of borrowing firms.

Federal Reserve Discount Window, primary credit activity (2003 – present)

Predictably, the use of the discount window rocketed upward early in the COVID outbreak. When markets calmed and uncertainty diminished, Fed lending through that facility gradually diminished, receding back to negligible levels. But more recently, throughout the second half of 2022, the use of the discount window began rising. The big question is: is what we are seeing merely an increase in exceptional, non-crisis borrowing, or is there a new financial crisis brewing? The two-year blackout on public disclosure of the identity of the borrowers makes considering the possibilities a particularly speculative exercise.

Lending at the discount window is done in exchange for collateral, as previously mentioned, and at above-market rates. (Much of what the discount window contemplates is consistent with Bagehot’s 1873 rules for central bankers, including “lend freely against good collateral at a penalty [interest] rate.”) It is certainly possible that the activity at the window is taking place as a backup (rather than a regular source of finding), as the primary discount window function requires. It may also be that lending is being extended to depository institutions not eligible for primary credit, as the secondary credit function of the discount window allows for. And, it is certainly conceivable that the vagaries of banking in an inflationary period have exacerbated the ordinary, seasonal requirements of firms facing such.

VIX Index, S&P 500 Index, US Dollar Index, and US High-Yield/10-year Treasury Yield Spread (2022)

But 2022 was a year uncommonly flush with exceptional stressors, especially for financial institutions. It began with a massive conventional war in southern Europe, which led to rising global tensions. Equity and fixed-income markets plunged, commodity prices skyrocketed, and between the dollar’s rise and other currencies tanking, foreign exchange markets experienced generationally high levels of coincident volatility. A brief recession hit the United States, as the highest inflation to strike the US in forty years was met by the fastest Fed interest rate hikes ever. In addition to all that, the cryptocurrency sector snatched long-held skepticism from the jaws of begrudging public acceptance with a drumbeat of scandals and plummeting coin prices.

In light of that backdrop, the idea that there may be a financial institution (or institutions) quietly fighting for survival cannot be ignored. One imagines that most accountants, controllers, and Chief Financial Officers currently on the job have experience from the economic conditions that prevailed throughout 2020, and that a substantial number of those have been around long enough to remember the 2008 disaster. Few of them, however, are likely to have been in their present roles during the 1970s, when inflation raged and interest rates see-sawed constantly. Inflation accounting and hedging interest-rate exposure were, as of the start of 2021, skills not in demand for US-based firms in a very long time. The idea that a financial institution, commodity marketer, or hedge fund, or a group composed of such, might need emergency liquidity is well within the spectrum of what’s imaginable.

Federal Reserve Discount Window, primary credit activity & Fed Funds Rate Target midpoint (2021 – present)

The fact that the amounts being borrowed at the discount window are rising in an oscillatory fashion with progressively higher “highs” and higher “lows” hints, while not conclusively, that the amounts being borrowed are increasing as the Fed increases rates. The idea that rapidly rising interest rates would strain a firm used to borrowing at the ultra-low rates which have prevailed for 15 years seems intuitive, although the sawtooth pattern requires additional conjecture. Any firms with large fixed-income portfolios are likely to be experiencing mark-to-market losses and consequently need to shore up their balance sheets. And while the tremendous losses associated with cryptocurrency assets and firms following the Luna and FTX collapses are not likely to affect depository institutions directly, their borrowers (and probably depositors) are certainly not as fortunate.

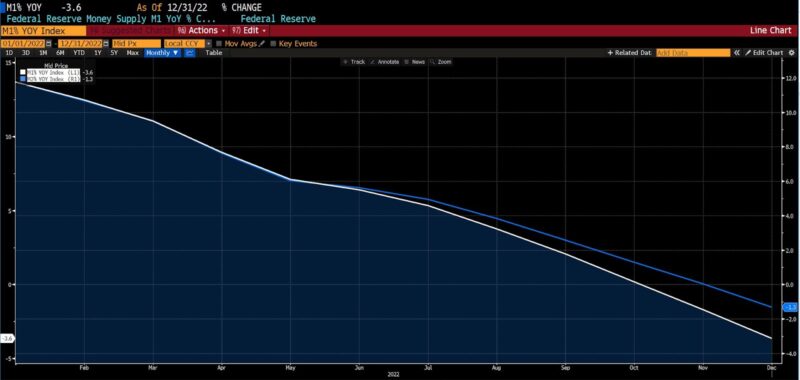

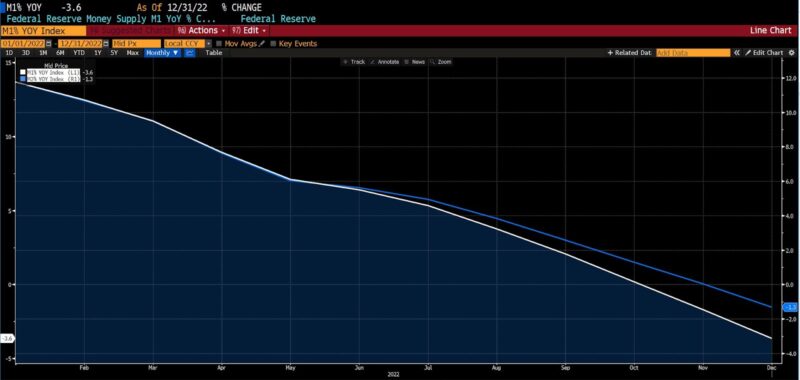

Recent data shows that the year-over-year rate of growth of the M2 money supply turned negative in November 2022; the M1 money supply followed in December 2022. For the first time since 1994, almost 30 years ago, the money supply is contracting rapidly.

Year-over-year percent rate of growth for monetary aggregates M1 & M2 (Jan – Dec 2022)

Thus monetary conditions are changing swiftly, and financial conditions may be even tighter under the hood of banks and financial institutions than they appear to be on the surface.

Forewarned is forearmed, but over the last two decades permabears have become impossible to parody. Nothing is conclusive yet. In about 18 months, the identity of the firms which have been tapping the Fed’s discount window starting in March 2022 will become publicly available. If those funding requests simply stem from navigating the ongoing effects of the economic maelstrom of 2022, we’ll learn at that time. If something worse is brewing, much sooner.