In June, the collapse of Terra Luna shook the foundations of the cryptocurrency sector. The contagion that followed drove a handful of other major firms, including Celsius, Voyager, and Three Arrows Capital out of business. But assumptions that the worst had come to pass, and that the wheat had separated from the chaff, were premature. The bankruptcy filing of FTX has even more fundamentally damaged perceptions of the asset class, and sent valuations tumbling to lows not seen in several years.

Comparisons with the collapse of Lehman Brothers and Enron Corporation were inevitable, but underestimate the proportional magnitude of the disaster. While Lehman was emblematic of the impact of subprime investments on the financial sector, and Enron of off-balance-sheet financing among newfangled energy companies, the FTX fiasco calls into question the entire crypto complex. In fact, the FTX situation more closely resembles the crisis at MF Global some years ago, which involved a proprietary trading division dipping into customer accounts to meet funding requirements. Alameda Research, allegedly a crypto-trading firm, appears to have not traded, but rather made venture capital investments, allegedly transferring and using FTX customer funds for various corporate purposes.

FTX (and Alameda) founder and CEO Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) saw a rise describable only as meteoric. The firm, started in 2019, was recently valued at over $30 billion. SBF was a 30-year-old billionaire, quickly compared with Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, and JP Morgan. For a time, FTX was inescapable: The logo was affixed to the shirts of Major League Baseball umpire uniforms and plastered on the Miami Heat arena. Tom Brady, Gisele Bunchen, Steph Curry, and other celebrities had advertising and marketing deals with the firm. And with the kind of irony that only financial markets provide, a Super Bowl commercial (cost: $30 million) in January 2022 featured actor Larry David responding to the assertion that FTX is “safe and easy” with “I don’t think so.” Life does indeed imitate art, at times. The firm is now bankrupt, assets are lost and missing, and SBF seems, as of this writing, to be in hiding.

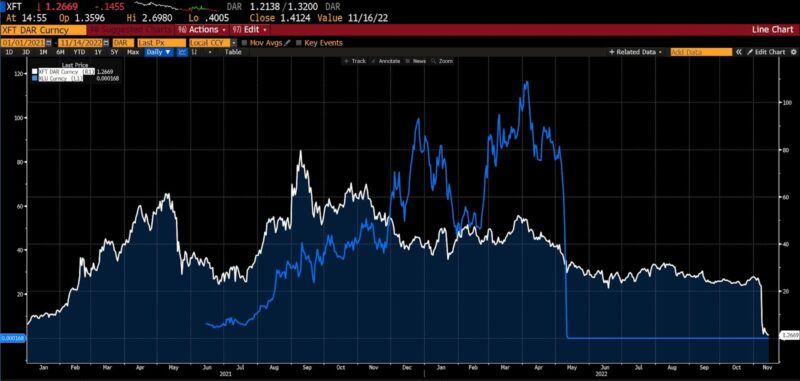

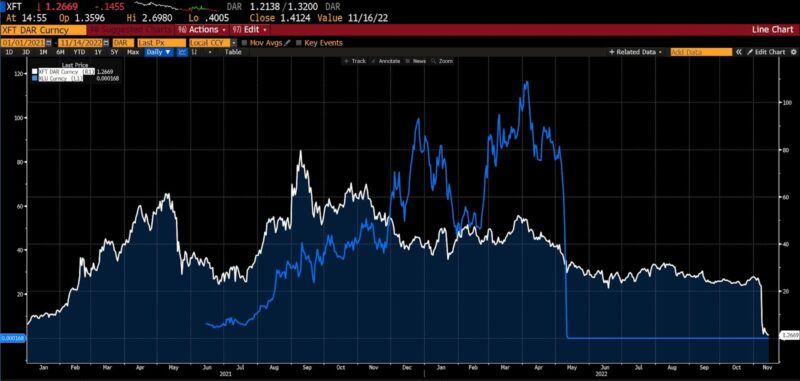

LUNA token vs. FTT token (2021 – present)

The FTX implosion, on top of other debacles and hacks this year, has led some to question whether there’s “anything about crypto that is as it seems.” Indeed, SBF’s humble, geek-chic image (unruly hair, unpretentious attire, driving an unremarkable vehicle) presents a picture of guilelessness.The emergence of a simple (if highly analytical) figure using cryptocurrency trading to selflessly tackle changing the world was no doubt irresistible to an increasingly left-leaning financial establishment. A fawning article at Sequoia Capital was quickly deleted as revelations regarding FTX emerged, but has been retrieved via web archive. Printed, it runs to over 30 adulating pages.

At odds with that narrative are a private jet, a sprawling penthouse in the Bahamas, and millions upon millions of dollars spent on purchasing influence in Washington, DC. Various sources have reported that SBF’s political contributions have been to both sides of the aisle, which is certifiably correct: he gave just under $36 million to progressive candidates and $105,000 to conservatives.

Throughout 2022, SBF’s lobbying efforts focused on politicians supporting the crypto regulatory framework of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). That makes sense, as SBF had drawn up and promoted a regulatory plan which, unsurprisingly, favored FTX’ business model. But the heavy lobbying, which led to SBF being the second-largest donor in the 2022 midterms, may have had more pressing origins. As the Wall Street Journal reported on November 9th, FTX had been under investigation by both the Securities and Exchange Commission (the alternate regulator to the CFTC) and the United States Department of Justice, since the summer.

The rules he promulgated would’ve, by one account, given FTX and its subsidiaries “a monopoly.” It would also have done serious damage to the massive array of decentralized finance (DeFi) and other such firms built over the last few years. What is unique in this instance is the immediate response by those which the proposal would’ve hamstrung. SBF’s regulatory proposal was so shamelessly self-dealing that it precipitated the entire unraveling of his empire – financial, technological, and political. Tory Newmyer of the Washington Post chronicled the tipping point:

Many crypto die-hards viewed [SBF’s] overtures to Washington as a betrayal of crypto’s founding mission. That set the stage for his most formidable adversary–Changpeng Zhao [CZ], chief executive of Binance, a rival crypto exchange–to crush him with stunning and decisive swiftness. On Sunday [November 6th] Zhao announced that he was selling off his investment in FTX: $580 million of a crypto token FTX has been using to prop up its debts. ‘We are not against anyone,’ Zhao wrote on Twitter. ‘But we won’t support people who lobby against other industry players behind their backs.’

CZ’s liquidation triggered a wider, more frantic exodus, and in turn, the discovery that withdrawal requests could not be met. An explicit attempt by an industry leader to erect insurmountable barriers to competition by commandeering legal and regulatory resources is far from unprecedented. But it certainly speaks to a sophistication that belies the ‘innocent visionary nerd’ role so actively marketed (see also Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos, Adam Naumann of WeWork, and Vlad Tenev of Robinhood.).

A nearly identical version of this sleight of hand has been going on in the rapidly expanding influence of the purveyors of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) philosophies. There is, as well, a direct connection between SBF and ESG: the FTX Foundation. Acting as the major conduit of his “effective altruism” donations, the list of supported causes offers few surprises. It launched in February 2022 (roughly the same time as SBF’s Beltway pavement-pounding began) and planned to support selected causes to the tune of $100 million per year, up to $1 billion over the next decade. Climate change, animal welfare, future pandemic prevention (and other causes) were SBF’s primary focus.

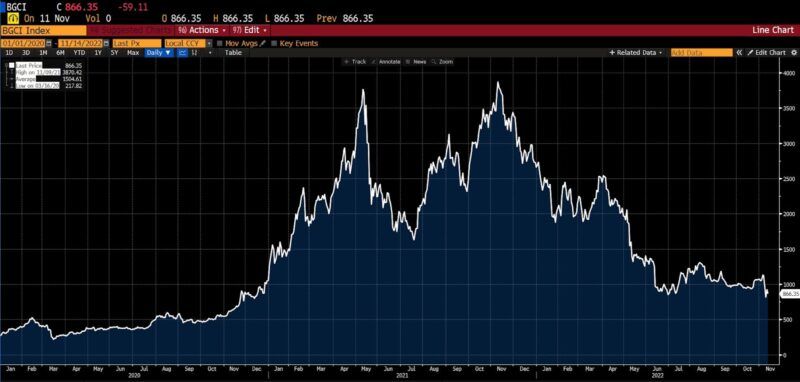

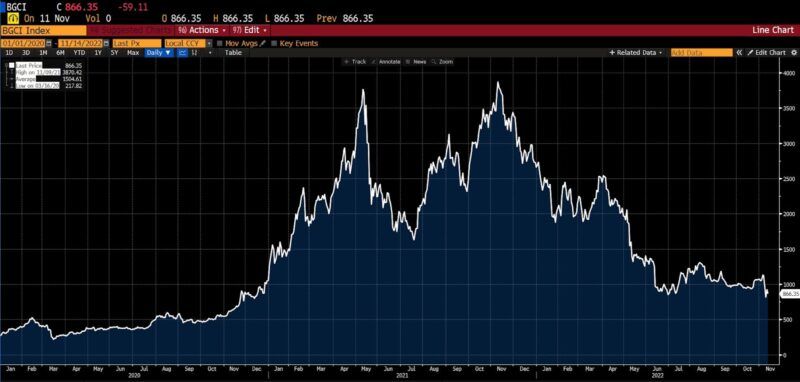

Bloomberg Galaxy Crypto Index (2020 – present)

It is impossible to square “effective altruism” with the surreptitious use of customer funds to cover costs and losses associated with personal, high-risk trading and investing activities. One use of customer funds was, evidently, a personal $7.3 million bet that Donald Trump would lose an election in 2024. For a businessman, long before saving the whales or shrinking carbon footprints, there is no “altruism” more fundamental than treating customer deposits with probity.

More hypocritical still are SBF’s direction of cryptocurrency activities at buying influence with government officials. It is an undertaking wholly antithetical to core, founding principles of Bitcoin itself. Despite recent attempts to reframe crypto development as a component of far left, techno-utopian projects, Wendy McElroy points out the unmistakably libertarian focus of Bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto.:

Satoshi’s forum posts are further evidence of his politics. The remarks are anti-banking and critical of government while acknowledging Bitcoin’s appeal to libertarians:

• Anti-banking. “Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with hardly a fraction in reserve.”

• Anti-government: “Yes, [we will not find a solution to political problems in cryptography,] but we can win a major battle in the arms race and gain a new territory of freedom for several years. Governments are good at cutting off the heads of centrally controlled networks like Napster, but pure P2P networks like Gnutella and Tor seem to be holding their own.”

• Pro-libertarian. “[Bitcoin is] very attractive to the libertarian viewpoint if we can explain it properly. I’m better with code than with words though.”

Governments, unlike markets, are neither effective nor altruistic.

The vast majority of ESG funds and firms are similarly misdirective. Freewheeling use of terms like “sustainable” obscure a wide variety of investment activities, some decidedly at odds with common public notions of “green” investing. Between 2019 and June 2022, some 65 US funds were re-branded as “sustainable,” without any consensus as to the meaning of the term. In the case of the Blackrock Sustainable Advantage Large Cap Core Fund, fund holdings included both Halliburton and Exxon Mobil stock. Financial Adviser cites Bloomberg’s Silla Brush in describing how at least one of ESG’s most indefatigable corporate virtue signalers has lobbied for broader and more malleable definitions

Blackrock executives … urged the SEC to avoid ‘prescriptive definitions’ for terms like ESG … [saying that it] describes a broad investment strategy, rather than a specific type of investment … In an October letter about Blackrock’s broad plans, lawyers for the funds told SEC staff that the ‘sustainable’ in its fund names didn’t suggest a focus on any particular type of investment, industry, country, geographic area, or tax status. The newly renamed fund also recast its mission, telling investors it would pick companies better positioned to capture ‘climate opportunities’ relative to those in a broad benchmark.

Its fourth-largest holding, in recent filings, is Chevron Corporation. Among other holdings are Exxon Mobil, Marathon Oil, Valero Energy, and Murphy Oil.

But if vacuous and opportunistic definitions of ESG and sustainability seem to diminish clarity, rest assured that the difference in fee structures between ESG/sustainable and non-ESG/”unsustainable” funds is crystalline. In mid-2021, Bloomberg reported that:

the $4.3 billion Vanguard ESG US Stock ETF, which has had a 99.7 percent correlation to the S&P 500 since it was launched three years ago [charges a] 12-basis-point fee compared to 3bps for Vanguard’s $222 billion S&P 500 ETF.

Investors are encouraged to consider how paying four times the normal management fee for a fund which is materially the same as the standard-weighted index combats climate change, delivers equity, or fosters inclusive governance. More recently, Harvard Business Review credited the compression of management fees (a consequence of rapidly increasing competition among asset managers) with the hasty embrace of greenness and sustainability, as ESG funds charge fees which are, on average, 40 percent higher than non-ESG funds.

S&P 500 vs. S&P 500 ESG indices (2019 – present)

While ESG offers countless other absurdities, this excerpt from a December 2020 Wall Street Journal editorial board piece points to a glaring issue with a corporate governance stipulation:

The more we think about the new racial, gender, and LGBTQ mandates for corporate directors that NASDAQ announced … the more absurd they seem. How is a company supposed to find out if a board candidate is gay if that isn’t already known? Is it supposed to hire private detectives to look into it? Once that person joins the board, does the company have to broadcast his or her sexual orientation in the annual report so progressives can be satisfied that the quota is met? We could go on…

Not two months before SBF’s empire came crashing down, the aforementioned Sequoia Capital article described him as having a “savior complex,” “liv[ing] his life by a calculus of altruistic impact.” As is often the case, beneath a warm patina of virtue signaling and noblesse oblige are decidedly less-idealistic machinations: rent-seeking, influence-buying, and greenwash. FTX and its subsidiaries, guided by SBF, had as much to do with “building a flourishing future” as ESG does with “creating a livable planet.” As a firm and ideal, respectively, both cultivated high expectations, yet generated waste and loss in their wake.

For both FTX customers and firms voluntarily suffering under the yoke of ESG compliance, it is probably too late. But more cardboard saints are sure to be anointed. Listen not to their words, nor be swept up by the promises they make, but rather watch what they do. Watch closely, with regularity, and always follow the money. For as HL Mencken wrote, the “urge to save humanity is almost always a false-face for the urge to rule it. Power is what all messiahs really seek: not the chance to serve.”