Traditional capitalist investors seek steady returns on investments with little risk of failure. Venture capitalists, however, invest in an array of risky but potentially high-return projects. Similarly, traditional academics seek safe, recognized lines of research that appeal to academic search committees and book publishers. Venture academics, on the other hand, seek a completely new line of inquiry with high potential for impact, but also high risk of failure.

A venture academic is a person who might write every third peer-reviewed paper on a topic that is completely new to them. They likely have a standby field of research where they know just about everything and feel at home, but there’s a good chance that this field of research is dry from time to time, and it makes sense not to keep plowing the same field, but to invest time and effort elsewhere. Venture academics have a more demanding approach to work, partly because they recognize the value of time and the trade-offs of working on multiple lines of research.

When entering a completely new line of research, a scholar needs to read the relevant literature, and learn standard methods and approaches to the topic. A venture academic sees an advantage in the challenge of learning new or different ways. Interdisciplinary cross-pollination of ideas often leads to new insights, and sometimes, to easy publications. Even in failure, venture academics see benefit in this work, knowing that what they have learned about a different field and a different method might come in handy on another project later on.

A venture academic might consider, every once in a while, writing a review of an unknown book from a lesser-known publishing house. The world does not need a 51st published review about the new flashy book from a famous professor at a big university. A review of a book by an unknown scholar, published by a small press, might disappear into the ether, but it is also possible, if that is the only review of that book, that many people might give the book a look. Once when I, and no one else, reviewed a book that was assigned to a number of college classrooms. Every September and October, when the book is assigned, hundreds of students from these classes find the review on my blog. By reviewing the work of a lesser-known scholar, that scholar will inevitably find your review, and if it’s positive, print it and put it on his refrigerator. He might also contact you and befriend you. In the long run, as you occasionally review the work of lesser-known scholars, one or two of them might rise in the field and remember the help you gave them. Meanwhile, your review of a famous scholar’s book will sink into the ocean, and the famous scholar will never contact you nor care, one way or another, what you had to say about his book.

It is also possible to be a venture academic in the classroom. Instead of repeating that stale set of lesson plans from last year, add a new lecture or two, or a discussion day, a workshop, or a field trip that is just a little out of the ordinary. It is possible that the new assignment will backfire, but if even one out of ten innovations in the classroom succeed, over time, you will have built a unique, successful class. A venture academic seeks ways to use the combined power of his students in fruitful research projects, and to incorporate research and teaching.

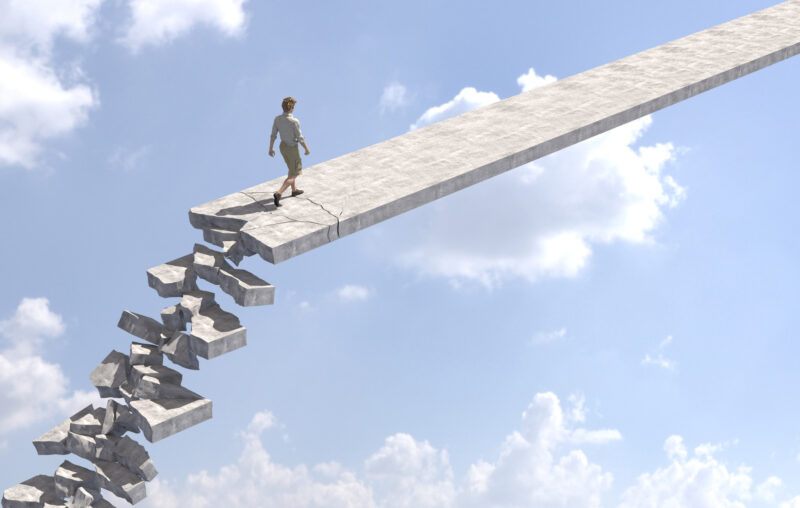

Failure is a major part of being a venture academic, just as it is with being a venture capitalist. Failure or rejection on one project does not spell doom for venture academics, because they are able to absorb a loss and move on to other projects. This is a strategy of many eggs in many baskets, with the hope that some will hatch. This is especially useful for academics who are not earning degrees at top institutions. The academic placement rate of graduates from non-elite universities is abysmal. What does becoming a venture academic do? Simply put, it gives you more opportunities, expands your network, and makes for a much more interesting academic experience.

One of the interesting paradoxes of venture academics is that they spread academic risk by dipping into new fields of inquiry, providing a buffer against the total collapse of their career. A venture academic is much better-prepared for the job market than a traditional academic because he has more options when things don’t work out. A traditional academic who writes, researches, and teaches on only one topic, say the history of the Civil War, can only compete for academic positions to teach the Civil War. However, a venture academic, who writes a dissertation on the Civil War, but who also publishes an article on the economic history of the Progressive Era, and teaches a class on the history of China, has more options open when he discovers there are only three Civil-War-history job postings in a year and some four hundred qualified candidates applying for them.

Survivorship bias in academia is strong, and it is easy for a graduate student to think that everyone who publishes a decent biography of Thomas Jefferson is going to get a tenure-track job, since, after all, everyone that he has ever met who has written a biography of Jefferson is a tenured professor. Most tenured professors today took a traditional low-risk approach to academia, but so did most failed academics, and what distinguishes the two is rarely just merit, but can be a host of things from luck to discrimination.

The venture-academic approach is not for all academics. It requires significantly more effort than the traditional route. Early-stage academics who have not yet published, or who haven’t published much, need to first establish themselves in one field, before they can work on projects in a variety of fields. As well, people in comfortable positions rarely take risks. Risk averse tenured professors might not be motivated to inquire into new lines of research when they can publish on the same old topic that they’ve been writing about for years. Why work hard if you are already at the top, or if you see no hope for advancement?

What percentage of academics today are venture academics? I’d say fewer than 10 percent, but the number is growing, especially as competition in certain fields heats up and more publications and credentials are necessary for success. Relative to workers in almost any other occupation, academics are by nature risk-averse, even as they promote an ideal of radical, world-changing research. Colleges and universities also are a lot more stable than most other firms, and they rarely go out of business, and almost never without a long fight. But academia remains a game of risk and reward.

Like any prudent investor, venture academics cannot invest in research projects willy-nilly, with only a prayer that one might succeed. But, by diversifying their research, and working on multiple projects on new, different topics, venture academics have a chance to make a greater research contribution than if they were to work in traditional ways.