For those in the classical liberal fold, a great deal is rightfully made of “methodological individualism”– the concept that it is the individual, rather than the collective, the class, or the society who is the primary actor underlying social phenomena. The idea undergirds the most sweeping revelations in social sciences, from theories of marginal utility to the inadequacies of Marxian macroeconomic planning. It is the concept of the individual qua individual that helps us understand the workings of our world. Without diminishing this vital insight, it is worth pointing out that it is not, precisely speaking, true. Almost never do human beings live, think, or act solely as individuals–we are not, despite models to the contrary, rational independent actors. We are instead most usually pair-bonded, family, and community embedded agents.

“Individual preference,” however, is the primary analytical framework in economic theory for building models of aggregate behavioral outcomes. F.A. Hayek described intelligible individual behaviors as the “building stones” in “complex market structures,” in a nod to Carl Menger’s descriptions of “atomistic” human behaviors. This echoes John Stuart Mill’s claim that “people decide according to their personal preferences.” Paul Samuelson’s revealed preference theory holds that “consumers’ preferences can be revealed by what they purchase under different circumstances,” once again implying that these preferences are wholly individual. However useful these insights may be, it seems the framing of individuality may prevent us from grasping the full story.

Digging Deeper: the Relationship as the Actor

In relationships, individuals frequently alter their preferences for the sake of their fellow humans-or perhaps more accurately, the relationship itself. The line between each individual’s real preferences is blurred, and the preference is actually a reflection of some nebulous space between individuals. When an economist refers to an individual’s preferences, there is an underlying assumption that this individual derives greater utility from whichever choice they prefer. But how much of this utility is being shaped and informed by the partnership arrangements the individual is acting within? For instance, women account for some 65 percent –80 percent of American grocery-store purchases. A female shopper may be aware of her partner’s (or family’s) preferences, and may even seek to satisfy them diligently, but on the whole her purchasing choices will necessarily reflect some attenuated form of the specific preferences of multiple individuals. She is buying for the relationship, not merely herself or others per se.

Likewise, political choices may be tempered by the relational bond. According to rational choice theory, individuals make choices based on rational calculations that maximize their own self-interest. Yet this self interest may at times be less a function of distant political matters and more a reflection of dynamics closer to home. Partner A’s strong political views may sway Partner B into moderating some positions for the sake of comity. Or, perhaps, these very views might generate an excessive counter-response in Partner B, causing B to vote more extremely than would have otherwise been the case. In either case, are Partner B’s altered beliefs in line with B’s real preference or are they simply the result of the desire to align with A?

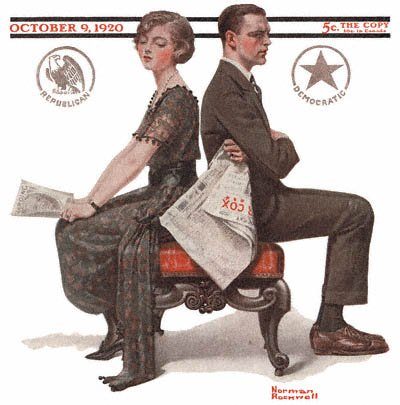

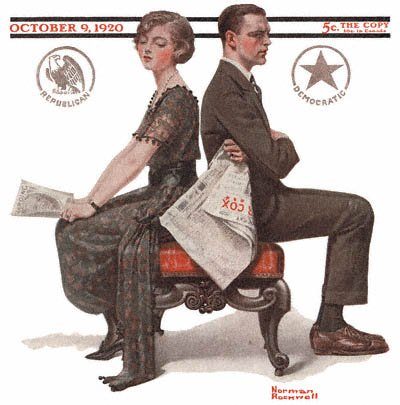

In Rockwell’s timeless illustration, the viewer can easily relate to the relational moment– firm individual convictions are clearly tugging at the pair’s bond. Let us imagine, for instance, that the husband, for the sake of domestic tranquility, eventually votes Republican or at least moderates his overt enthusiasm for Democrats. He is thus making a choice that does not truly reflect his actual preference. A pollster or economist, observing only the husband’s resultant “shift in preferences,” would likely be oblivious to the underlying reasons for the shift. Perhaps the negative utility derived from the husband’s personal sacrifice is offset by the gratitude his wife shows, or the improved dynamic in the relationship. It follows, then, that “revealed preferences” are not the preferences of the mere individual but instead reflect that of the relationship itself, as its own entity.

So What?

One might properly argue that, for purposes of understanding social phenomena, such internal dynamics are effectively moot since it is, after all, the individual at the end of the day who undertakes a given action. A family does not purchase an onion, and a couple does not vote for a candidate. Nevertheless, a growing body of research indicates that the topic is worth considering in an economic sense. Along the lines marked out by Michael Munger’s What Preferences Do You Want?, we wish to point out that an assessment of “individual” preferences can be misleading due to apparent empirical accuracy and more could be done using quantifying variables to assess relationships as a distinct entity. Indeed, as Munger states, the standard “modeling assumption [of preferences] means that we miss a lot of richness in the process of deciding what we want.”

Similarly, Margarita Gorlin and Ravi Dhar write that in “joint and individual decision-making…[a] relationship partner’s influence varies with the type of decision at hand,” but that influence can be real and measurable. Catherine Hakim’s women’s preference theory depicts the impact that “lifestyle preferences” have on women’s choices regarding “family work” versus “market work.” Hakim notes that new choices have emerged for modern women, in which they make labor-entry decisions based on “work-centered,” “home-centered,” or “adaptive” preferences centered around their loved ones. In so doing, she acknowledges what single males like Adam Smith, John Locke, or Isaac Newton did not: the nature of intuitive relationalism that defines the everyday reality of lived experience.

In short, by attending to relational preferences, we can make more informed conjectures about the actions of individuals, and hence societies. “Revealed preferences” may not always be the preferences of specific individuals, but instead reflections of the ineffable space between competing (however so gently) value sets. Overall, accounting for the influence of relational dynamics may help us better understand some of the more vexing behaviors left unexplained by an over-strict adherence to methodological individualism.