One of the difficulties inherent in writing are lags. Once ideas or predictions are on paper and in the public eye, they are memorialized; the vagaries of time and happenstance can convert them into something prophetic or ridiculous. It is a hazard inherent in going on the record, albeit a far lowlier one than many, indeed most professions face.

As this article is being edited, an estimated 130,000 Russian troops are massed on the border of Ukraine, fueling worry about an invasion. Recent reports indicate that combat aircraft and blood stores have been moved close to the troop buildup as well, further suggesting impending conflict. There are news blurbs about Kiev citizens arming themselves, and the Brent crude oil contract recently hit highs not seen since the fall of 2014. From the US, Western Europe, and their global allies, the response has been predictable: posturing and warnings. The response from Russia has been mostly to dismiss concerns while adding that the Donbas insurgency threatens its national security.

Both sides, of course, are challenging one another’s standing: Russia on the basis of Ukraine being a neighboring nation, and the US and Western Europe on the basis of Ukraine’s sovereignty. The least-heard stakeholder in the rising tensions, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, has accused the West of attempting to create panic while indicating that talks are continuing.

The roots of the Russia-Ukraine relationship are deep, complex, and far beyond the scope of this article. There are many social and cultural links between the two. But in considering people all over the world, geographic proximity, cultural similarity, or linguistic similitude do not imply integrity.

Pandemic Origins

Like the rest of the world, Russia was struck by the global Covid outbreak two years ago. At that point, the Russian government had been attempting to balance policies emphasizing growth and stability for some time. Being an energy exporter, its economy relies disproportionately upon oil and gas; commodity price swings impact Moscow’s revenue and spending potential. In the last 5-10 years, Russian President Vladimir Putin has put a particular emphasis on stability at the cost of growth. Russian per capita GDP is less than half that of the US, and although the comparison is somewhat inapt, the GDP of Texas is larger: in 2018, the US state’s GDP was $1.70T versus Russia’s $1.28T.

In response to the pandemic, the Russian government imposed a nationwide lockdown. That, of course, incurred an artificial recession. Not long after that, with the bottom dropping away from global oil demand, an oil price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia resulted in a veritable tidal wave of oil hitting world markets. The May 2020 West Texas Intermediate oil contract closing at -$37/bbl (barrel) is directly representative of the state of world oil markets at that point. With so much oil hitting virtually demandless markets, storage, rather than oil itself, became traders’ end games.

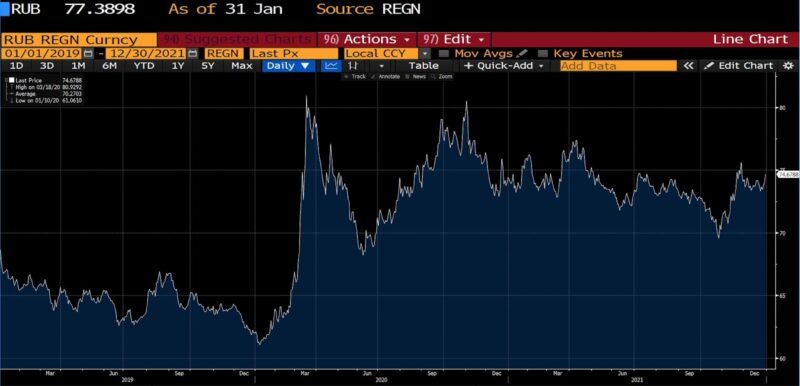

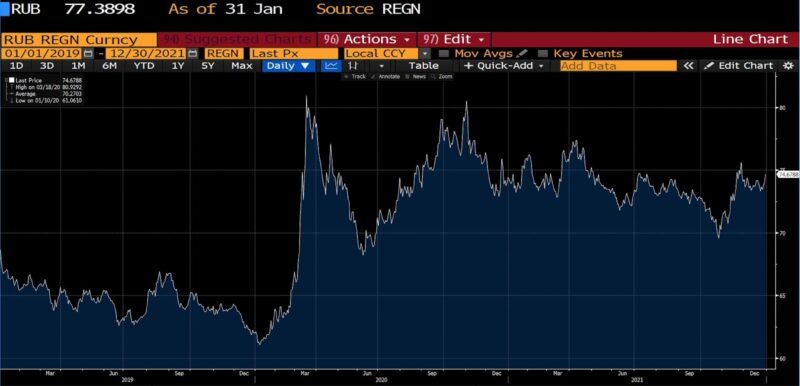

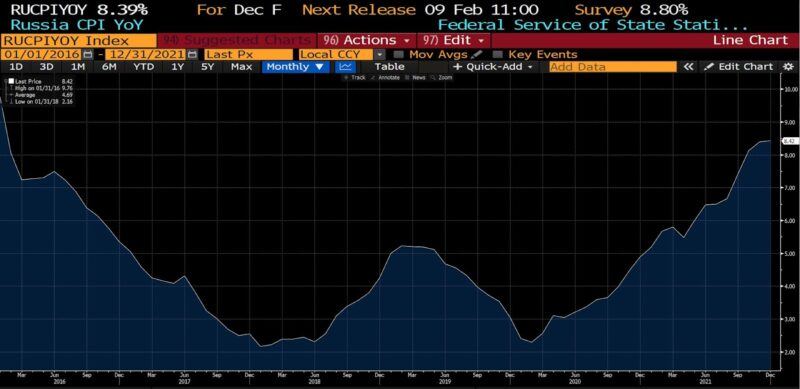

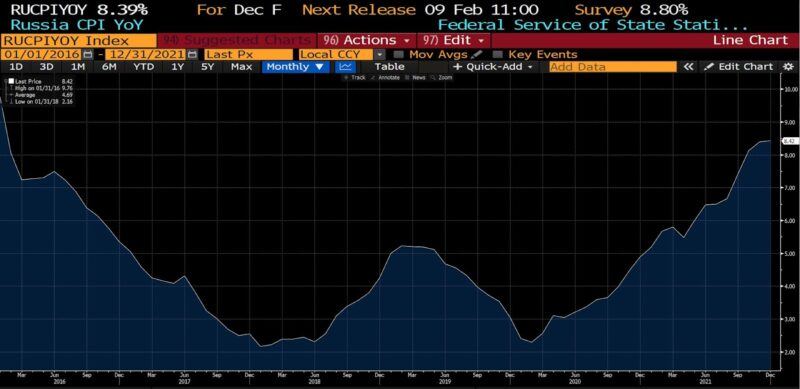

The Russian ruble, as it tends to, suffered in sympathy with a worsening energy outlook, with a 30 percent drop between January 1 and March 18th. Soon thereafter prices began to spike, rising from roughly 2.5 percent (Russia CPI, Federal Service of State Statistics) in February 2020 to nearly 5 percent by the end of the year. Also, by December 2020, the budget surplus which Moscow had expected to run (930 billion rubles/$11.4 billion USD) was a deficit. But it was another trend which arguably contributed to what is now happening along the border of Ukraine, and may or may not have developed by the time this is read.

RUB/USD cross (2019 – end of 2021)

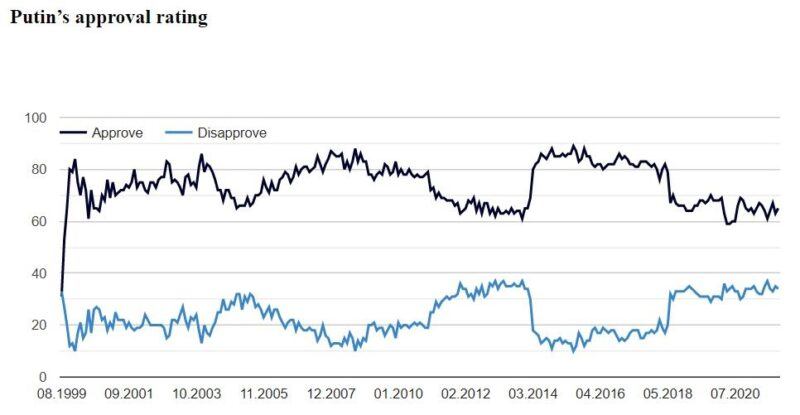

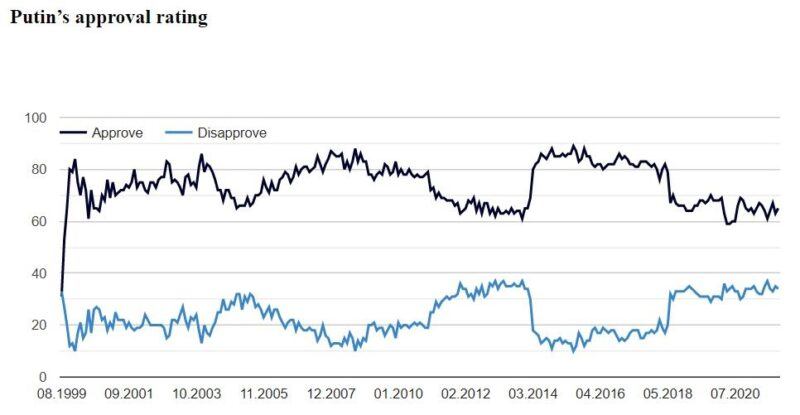

A decision was made by Putin’s government in Moscow for reasons that can only be understood via educated guesses. The central government of Russia chose to push most Covid policy decisions out to local regions. After the nationwide lockdowns and then a handful of tax breaks and interest-free loans, crisis mitigation efforts were delegated to regional governments. Whether that decision was a tacit nod to the benefits of decentralization or an effort to deflect criticism for ineffective policies, we cannot know for certain. But over the second half of 2020 and throughout 2021, two numbers as closely scrutinized within the Russian government as outside of it began falling: Vladimir Putin’s public approval and trust ratings, as measured by the independent (and often criticized) Levada Center.

Part of the growing disapproval of Putin’s handling of the crisis stemmed from the length of the lockdowns and the view that direct state aid was insufficient. On May 4, 2020, Russian football player Yevgeny Folov appeared on national television, saying:

What the president says on television is all nonsense. There are no real actions. When talking to real businessmen, one can learn that banks will never issue soft loans and will not give a loan delay. We are forced to stay at home, and there is no help from the state. People are being fined [for going outside]. People have no money, and the average fine is 5,000 [rubles; at that time about $80]. People are going a second month in a row without a salary. This is not the case in Europe. And we see how our police work: they just twist people’s hands or hit them in the face and take them away.

The slow decline of faith in the Russian government didn’t start with Covid, but rather began when 2018 pension reforms were put in place, resulting in (among other changes) an increase in the retirement age (more about this, later). In January 2020, the most extensive efforts at modifying the 1993 Russian Constitution began; it was only in March of 2020, though, that a clause allowing a sitting president to sidestep term-limits would appear. After being passed by the Russian parliament, Putin insisted upon putting the measure to a national vote; and to induce voter participation, such populist measures as a ban on gay marriage were included.

Putin took office in May 2000, and since then has swapped between roles as Russia’s president and prime minister to stay at the top of the power structure. Where he would’ve had to relinquish his office in 2024, he can now rule until 2036.

Mr. Putin’s political idyll was short-lived. As Henry Foy wrote for The Irish Times:

Just 10 days after winning a popular vote designed to depict the country as united behind its leader, protests erupted that instead demonstrated the level of simmering popular discontent. They also underscored the gulf between the president’s Kremlin and ordinary citizens after his more than two decades in power…The protests, spanning an unprecedented 18 consecutive days unhindered by local police, have left Mr. Putin looking detached and listless in contrast to his usual decisive and hands-on image…“The Kremlin has forgotten how to politically respond to issues like this. They are losing their ability to respond to societal discontent,” said Tatiana Stanovaya, founder of political analysis firm R. Politik.

“Society,” Ms. Stanovaya commented, “is beginning to impose itself on the Kremlin rather than the other way around.”

Oil markets soon recovered. But like most other nations in 2020, in Russia political promises to kickstart growth were abandoned. To their credit and underscoring the policy emphasis on stability rather than growth, an oil income “rainy day fund” was brought to bear on the hardship. (When Brent is priced over $40/bbl, a portion of oil revenue is set aside as a potential stabilizer in difficult times.) Although still unsatisfactory for many citizens, that fund helped expedite some of the economic recuperation. Nevertheless, there were early attempts to paint a rosier picture of the performance of Russia’s nonpharmaceutical interventions than facts warranted.

Russia has the world’s highest tally of coronavirus cases, but relatively fewer deaths…These promising signs, however, have been met by claims that the country’s official death statistics do not correspond to the actual situation in the country. Some outlets, including The New York Times, have reported that Moscow’s death rate may be more than double official numbers…Those who die at home are not examined and are not included in the official count…[and in late May] Riga-based Russian language outlet Meduza reported that, of 509 medical workers who responded to a survey, one-third claims they were instructed not to list pneumonia-related deaths as having resulted from Covid-19, even though pneumonia is a common illness when Covid-19 spreads to the lungs,

By the early summer of 2020, considerably darker tactics seemed to be at work.

Three Russian medical workers have fallen out of windows, two of them fatally, under mysterious circumstances in the past two weeks. Alexander Shulepov, a paramedic from the city of Voronezh, is in critical condition after falling out of a second-story window at a hospital where he was being treated for COVID-19 last Saturday. Shulepov had earlier posted a video online along with a colleague in which he complained of being forced to work even after testing positive for the virus. The colleague had earlier been questioned by police for allegedly spreading fake news after complaining publicly about PPE shortages…On May 1, Elena Nepomnyashchaya, head doctor at a hospital in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk, died of her injuries from falling out a window during a meeting about turning the hospital into a coronavirus treatment facility. Nepomnyashchaya reportedly opposed the plan because of equipment shortages. On April 24, Natalya Lebedeva, head of emergency medicine at Star City, the training base for Russian cosmonauts, also died after a fall from a window…Defenestration is also sadly not an implausible fate for critics of government policies in Russia. A number of journalists have also died after falling from windows under mysterious circumstances in recent years.

In January 2021, Bloomberg reported that despite a breather, the Russian economy appeared to be stalling again. It didn’t happen. In fact, last year Russia saw its strongest growth in 13 years, but by the end of 2021 Putin’s approval ratings remained close to their lowest levels in two decades. Inflation had risen steadily throughout the year, hitting levels last seen in 2016. And in the wake of the cyberhacking scandal, in April 2021 US sanctions for the first time targeted not just the personal fortunes of elites, but the country’s sovereign debt. By blocking the purchase of newly-issued ruble-denominated Russian debt, the strength of the recovery from Covid was muted. By late 2021, predictions for Russia’s economic health in 2022 were dialed back.

Russia CPI year-over-year (2016 – end 2021)

And it is at this point, in November and December 2021, that a deployment of Russian troops and equipment toward the border of Ukraine that began in March 2021 became a sizable, rapid build-up. In fact, some sources guess that through the second half of last year Russia’s offensive capability in the Western Caucasus doubled. Additionally, the

Russian deployment has been slow and deliberate. This allows Moscow greater freedom to select the potential timing of an operation while retaining some element of surprise. Of course, seasonal weather, hardening of terrain, the presence of foliage for camouflage, and other factors may affect the Russian calculus on what the optimal time might be for a military campaign.

Indeed, Russia may just be rattling its proverbial saber at the West. And the fact that any Russian move toward Europe and the US pushes oil prices up, which is good for Moscow, cannot be discounted. An invasion or conflict is by no means a foregone conclusion.

The Crimean Playbook

But although no one would or should allege a solitary causal factor, there is no argument that Covid isn’t a major factor leading to this development. As Daniel Sixto of the Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy summarizes:

Putin’s inadequate response to the coronavirus [has] eroded the trust between Russian citizens and the Kremlin…[his] attempts to demonstrate power and Russian order [have] only backfired, leading to increased unrest…[his] obsession to celebrate the World War II Victory Day Parade demonstrated [his] lack of commitment to initially tackle rising coronavirus cases in Russia…[and in] late August, Alexei Navalny, Putin’s leading opponent in Russia, was hospitalized after a suspected poisoning from the Kremlin. Russia’s poisoning of Navalny represents one of many acts of intimidation. This time, however, Moscow’s plans backfired, and the opposition leader’s approval rating surged…Putin’s inability to lead Russia amidst the Covid-19 pandemic left a power imprint on his legacy…[s]ince the virus reached Russia in late January [2020] Russia’s closest allies have turned on Moscow and anti-Kremlin protestors [have been] flood[ing] the streets…[V]oters won’t likely forget the effects of Covid-19 on their livelihoods, possibly mounting a considerable opposition in the 2024 election.

While Putin’s approval ratings didn’t fall as far as they have recently, between 2011 and 2012, there was a sizable drop. Then too, the growing perception was of an increasingly inert government unable to address citizens’ largest concerns. Daniel Treisman analyzes the fall thusly:

Between February 2011 and April 2012, the proportion [of the population] finding Putin “businesslike, active, energetic” fell from 51 to 39 percent. Fewer than 8 percent by 2012 found Putin pleasant, appealing, and charming or honest, decent, and not corrupt. Six weeks after his election, fewer than 40 percent of respondents thought that Putin would still have won the Presidency if Russia had “a free press and television, which could freely talk and write about abuses of the authorities.”

In 2012, Dmitry Medvedev and Putin swapped positions as Russia’s Prime Minister and President, respectively. The approval ratings of both fell further, and protests broke out across the country as allegations of broken promises and corruption swept through the popular mind. Throughout 2013, amid confrontations between the US over Edward Snowden’s asylum and intervention in Syria, approval ratings stabilized in the mid-60s; not bad, but far below the range from mid-2005 to late-2010 in which they had ranged from the mid-70s to the mid-80s.

In February 2014, when the decision was made to annex Crimea, Putin’s approval ratings sat at a tepid 69 percent. Within one month it had leapt by the greatest month-to-month amount ever, to 80 percent. And by the end of 2014 it was hovering close to 90 percent. By mid-2015, The Guardian reported that

Putin’s approval rating is at record levels, with nine out of ten Russians saying they have a positive view of their president. Putin had an approval of 87 percent in July, and an all-time high of 89 percent in June, according to Levada Center polling. Following a drop in popularity in 2012 and 2013, when Putin’s approval ratings dropped into the 60s, the Russian President’s popularity picked up again last year on the back of events in [eastern] Ukraine…Some 70 percent of Russians believe the country should stick to its current position on Ukraine, while 20 percent say it would be better to make concessions in order to avoid sanctions. 87 percent support the annexation of Crimea, and only 4 percent think that the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk should return to their pre-conflict status.

Not only did many Russians wholeheartedly support Putin’s move, but reliable opposition members did as well. Kseniya Sobchak, a television figure regularly expressing disapproval of the Putin regime’s policies, commented that the essentially bloodless operation might elevate him “in history to the level of a great [akin to Peter and Catherine, et al], and there’s nothing [anyone] can do about that.” And while a huge leap in public sentiment was not guaranteed, the Crimean push “tap[ped] into deep-seated nostalgia, not so much for the Soviet system as for the superpower’s imperial reach.” The Crimean annexation popularity boost lasted well into 2018.

Will Pandemic Failures Lead to War?

As noted earlier, a litany of geopolitical, historical, social, and cultural factors are at play in the Russian-Ukrainian standoff. Energy market disputes factor in as well. But could the Russian government’s poor performance during the Covid pandemic, resulting in plummeting public support, have played into the decision to stare down NATO?

Almost undoubtedly. In November 2018, Russian forces blocked access to the Azov Sea, and opened fire on several Ukrainian ships. Adam Taylor of the Washington Post wondered at that time whether

domestic concerns [could] be forcing Russia to take [that] aggressive stance? Russia’s economy is stuck in the midst of long-term stagnation, and a plan to raise the retirement age has proved unpopular with voters…Kimberly Marten, a Russia watcher at Barnard College, pondered whether with the sudden escalation in Azov, Russian President Vladimir Putin might be “provoking yet another international crisis in hopes of winning support at home.”…Indeed, when you look at polling from Russia and compare it with acts of Russian aggression, there does seem to be some sort of correlation…[T]here are two [other] important dates when Russia took foreign policy moves that may have been motivated by domestic popularity concerns: the 2014 annexation of Crimea, and the invasion of Georgia in 2008.

Russia is not, by far, the only nation for which the Covid pandemic starkly exposed a variety of limitations. In many, indeed most countries, the period between 2020 and the present has been punctuated by outright lies, partial truths, and the denial of readily apparent facts by state officials and international organizations. Conflicting messages, renewed propaganda, and brutality have frequently followed the discovery that policy measures wreaked unnecessary wreckage upon people’s lives and futures with little or no impact upon thwarting the spread of infection.

At this writing, it remains a fast-moving, tense situation. The US and its allies are allegedly preparing a withering raft of sanctions which may include a ban on financial transactions in any ruble-denominated debt, new or issued. Peace or an unhappily brokered stalemate may still result. Or Ukraine may become the point where a decision to project Russian influence into Eastern Europe forcefully by thrusting a thumb deep into the eye of NATO converges, awfully. In any event, this point will have come amid an uncountable series of influences. A major military power appears poised to attempt to wrest back the perception of irreproachable faculty to gin up public sentiment. Whether in volumes or a few paragraphs, history must reflect the role that one of many influences, a global pandemic, played.

It is 8:55pm EDT on January 31, 2022. Covid’s direct toll on human life and liberty has been monstrous, mostly for unnecessary reasons. One hopes upon hope that its indirect toll will be mollified, starting just north of the Black Sea.