When Nikole Hannah-Jones published the 1619 Project in August 2019, it initially came under an unfair line of attack from historians who took issue with aspects of its discussion of Abraham Lincoln. Hannah-Jones had correctly identified Lincoln as a supporter of black colonization – a common 19th century “solution” to slavery that involved coupling emancipation with the resettlement of the freedmen abroad in locations such as Liberia or Central America.

Lincoln’s speeches and writings contain dozens of unambiguous endorsements of colonization, which he intended to subsidize through the US government, albeit on a voluntary basis for the freedmen colonists. Though misguided in its aims, Lincoln’s brand of colonization was also motivated by his antislavery beliefs and specifically the notion that resettlement abroad would permit African-Americans an opportunity to enjoy the rights and freedoms that were denied to them in the United States. Nonetheless, Lincoln’s colonizationism has long been a sore spot for Lincoln scholars due to the complexities it introduces to the “Great Emancipator” political iconography. Several generations of historians have put their pens to work seeking a way to give Honest Abe an out where colonization is concerned. Most contend that Lincoln abandoned the scheme mid-presidency, reading an active repudiation into his public silence on the measure in the final year of the Civil War. Others even put forth the theory that Lincoln only advocated colonization as a political ruse – a “lullaby” to coax public opinion closer to the Emancipation Proclamation.

Reality is much more straightforward. In addition to being a sincere antislavery man, Lincoln was also a sincere colonizationist who meant what he said when he espoused this position. A substantial body of my own work on the Civil War era investigates this exact question, conclusively showing that Lincoln continued to pursue colonization schemes through diplomatic channels well beyond the Emancipation Proclamation, and likely into the last months of his presidency. When Nikole Hannah-Jones made similar claims in 2019, she was drawing directly on my work as a historian of that subject.

In fact, Hannah-Jones stated as much in a series of now-deleted comments as some of the other historian-critics questioned her claims about Lincoln and colonization.

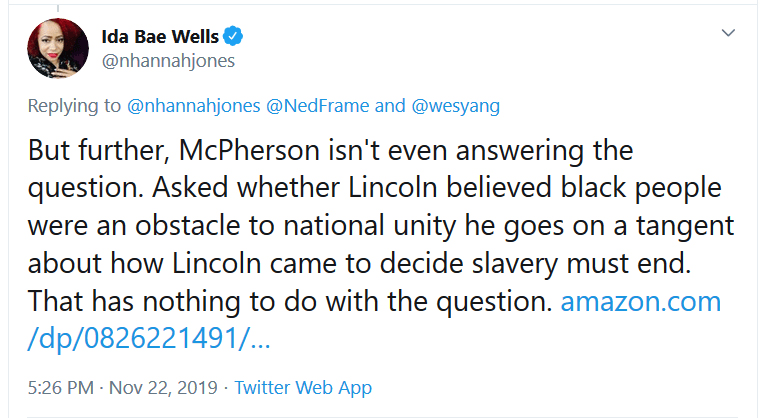

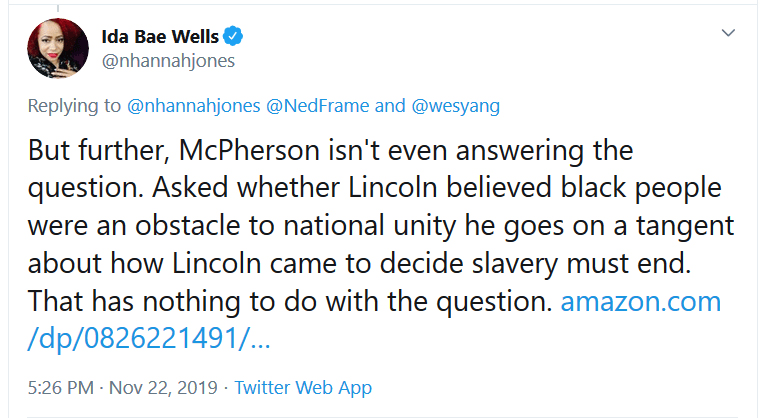

On November 22, 2019 she tweeted out a link to my co-authored 2011 book on the subject, Colonization After Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement.

Three days later, Hannah-Jones wrote, “For instance, recent scholarship shows Lincoln did not abandon colonization at Emancipation but worked on it until he was assassinated.” In another comment, she criticized historian James McPherson’s “dated scholarship on Lincoln ending his efforts to colonize black people at Emancipation” (McPherson is one of the main proponents of the above-mentioned “lullaby” thesis). Quite the contrary, Hannah-Jones continued, “recent scholarship shows [Lincoln] continued these efforts until his death.”

In both cases, the “recent scholarship” that she referred to was my own work, which I summarized in a series of articles in 2012 and 2013 for Hannah-Jones’s own employer, the New York Times.