“What is the best defense against violence?” polymath entrepreneur Chris Rufer once asked.

Though I’m not much of a gun enthusiast, my thoughts automatically turned to Messrs Smith and Wesson. After all, the Second Amendment is designed to encode our right to self-defense. But then I figured that answer must be too obvious.

“The police?” I replied with a chuckle.

“Morality,” said Rufer. “The best defense against violence is to minimize the number of people in the world who are willing to use it.”

For a long time, that answer felt off somehow. Some people are just cruel or predatorial in a way that morality won’t change. But I am coming around to Rufer’s perspective. I’m not saying people shouldn’t be prepared to defend themselves. Instead, we should give the idea of preemptive moral training due consideration. To the extent there is something to it, we have work to do.

But let me not get ahead of myself.

The Moral Vacuum

It’s no secret that Americans are losing their religion—particularly the young. And I can say that, despite being an unbeliever myself, I’m not sure this has altogether been a good thing.

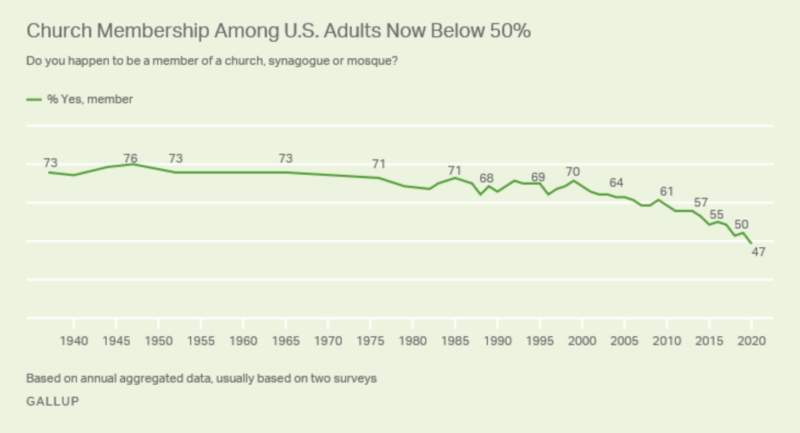

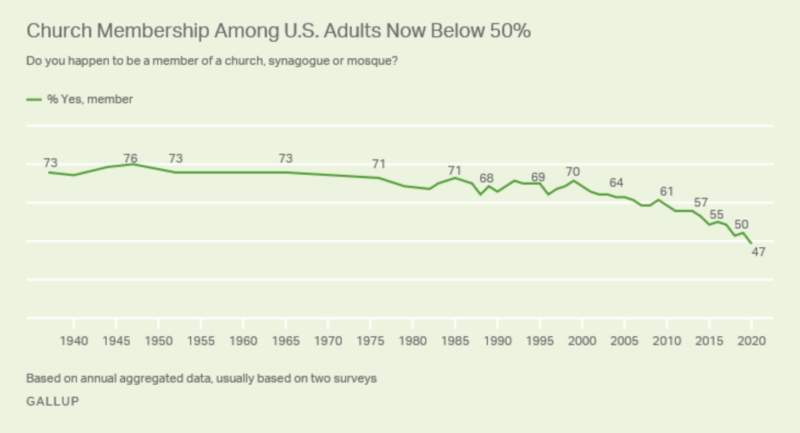

According to Gallup, only 47 percent of Americans attend a church, synagogue, or mosque, which is down from 73 percent when the pollsters first asked the question in 1937.

Despite humanity’s history of religious wars and persecutions, most major religions offer some set of moral guidelines — virtues, values, and guidance on how to live a good life. Variations on the Golden Rule appear in almost every faith. But as more Americans have left organized religion, they have also abandoned a source of moral teaching and moral community.

Nature abhors a vacuum, the saying goes. So in the absence of religion, where are these lost souls turning for their morality?

My hypothesis: politics. The Church of State.

In other words, people are turning to politics as a kind of ersatz religion. They seem to think that identification with some party platform or platitudinous yard sign is enough. But the virtues and values of politics — to the extent these exist at all — are anemic at best, deadly at worst.

- Instead of practicing compassion, politics prompts us to outsource our compassion to distant capitals.

- Instead of being personally responsible, politics asks that we ship our responsibilities off to algorithmic tax and transfer schemes.

- Instead of figuring out how to improve our lives, politics invites us to belly up to a trough of stolen goods.

- Instead of facing our fears and addressing our community’s needs, we imagine that faceless bureaucracies are somehow protective daddies and caring mommies.

- Instead of setting good institutions for production and trade, politicians horse-trade with other people’s money.

- Instead of creating value or sustainably serving others, politics legitimizes the expropriation of the productive classes.

- Instead of doing good in person, politics prompts us to seem good online.

- Instead of joining with our neighbors in solidarity or community, politics pushes people to engage in partisan warfare.

Whatever your partisan affiliation, you will find little moral good in politics, which is why most people think of it as a necessary evil. We have to consider the possibility that it’s just plain evil.

Persuasion or Compulsion

If you want someone to act, there are only two ways to do it: persuasion and compulsion. You can use “sweet talk,” or you can make her an offer she can’t refuse. In other words, you can use means that prompt her consent or means that compel her.

At some level, persuasion is the language of morality, and compulsion is the language of politics. “You ought to do X” is designed to persuade you. “You must do X, or else…” is a threat of violence, even if it’s encoded. As Yale law professor Stephen L. Carter reminds us:

“Law professors and lawyers instinctively shy away from considering the problem of law’s violence. Every law is violent. We try not to think about this, but we should. On the first day of law school, I tell my Contracts students never to argue for invoking the power of law except in a cause for which they are willing to kill.”

Carter’s admonition should extend well beyond lawyers. Every single one of us must be reminded that politics is inherently violent.

Politics and morality are what you might call overlapping magisteria. That is to say, each domain has certain qualities that make it distinct, but there are — or at least should be — crucially important areas of overlap. More specifically, politics needs more morality, though it’s not clear that morality needs more politics. Indeed, I am committed to a liberal doctrine that includes minimizing politics to the greatest possible extent.

Why would anyone support such a doctrine?

Said simply, to engage in politics is to deal in the currency of threat. Therefore, it’s not hard to imagine how the world might be better for any given person if more human community members chose persuasive over compulsory means. The Vedics call this ahimsa, or nonviolence. Whether in our individual thoughts, words, and deeds — or in architecting our systems of governance — we should always seek nonviolence. It is the prime moral teaching.

So, I’m coming around to the view that market liberals have placed far too much emphasis on politics, policy, and punditry. It is time to place greater emphasis on morality, meaning, and mind control.

Morality, Meaning, and Mind Control

Morality is the discipline of being good. I believe that, at the most fundamental level, being good starts with a commitment to nonviolence. We should add the conscious, continuous practice of integrity, compassion, toleration, stewardship, and curiosity upon that foundation. Perhaps there are more, but these six will take us very far, indeed. One might go as far as to say that if we could start a cult of these six spheres and make everyone a convert, we’d be far closer to heaven on earth than whatever image burns in the minds of ideologues.

Meaning is the stuff of life. It’s why we are engaged in our various pursuits, and it is how we see ourselves figuring into the bigger picture. When each of us reflects on our own lives, perhaps through the lens of the septem circumstantiae (who, what, where, when, how and why), we can contextualize ourselves along several dimensions. In other words, by answering these questions about yourself in silent reflection, one forms a certain kind of picture of herself and her place in the world. While such an exercise is mostly subjective, it can confer meaning in ways we might call transcendent. Absent an individual search for meaning, one can feel cut adrift, or worse, become susceptible to groupthink and submission instincts.

Mind Control sounds nefarious, but I’m using the phrase in the literal sense. Specifically, I refer to our ability to control our emotions and our behavior. I refer to the Viktor Frankl epigraph above, for between stimulus and response there is, indeed, a “space.” And through practice, we can expand that space such that we grow and develop as moral beings. In a world saturated with victimhood narratives and sorry excuses for everything, there is little left to enlighten, ennoble, or inspire.

Part of the liberal project, then, must be to remind every person that she needn’t be a victim of systemic or structural anything. She is self-possessed–an agent capable of architecting meaning, practicing morality, and inspiring others to do the same. The more people who are engaged in morality, meaning, and mind control, the fewer people will be looking to politics for their place in the world.

And in so doing, she provides just a little more of the best defense against the world’s violence.