Let me take you back to January of this year. Biden had just been inaugurated, the U.S. Capitol attacks were on everyone’s minds, the worst of winter was upon the Northern Hemisphere, and Covid measures kept upending people’s lives. The Texas energy crisis and cold snap hadn’t quite happened yet, but another portion of American life was already heating up, one that would forever change how we look at markets, brokerage firms, hedge funds, and the meaning of financial wealth.

On the first day of trading for the year, January 4, the shares of the failing brick-and-mortar store GameStop (GME) opened at $19, closing about 9 percent down for the day. The long end of the Treasury bond yields would rise a little toward the end of the month, but nothing too extraordinary. Most financial eyes were on Bitcoin, trading at around $33,000 by the beginning of the year, after having blown past its 2017 all-time-high over the holidays – and then some over. The quick run-up to $40,000 in January looked unusually fast even for this fast-moving asset: was it an obvious bubble or an omen of bad monetary things to come?

In the background, unbeknownst to the elites on Wall Street, a financial market revolution was in the making: a not-so-organized plot to take down some Wall Street kings, stick it to the man, reclaim control, and many other such colorful platitudes in which revolutionaries wrap their assaults. Simmering wide open on a Reddit forum called WallStreetBets (WSB) were all manner of frustrations – with inequality, with dead-end jobs, with Covid measures shattering everyone’s life plans. Among the angry-sounding comments were a handful of fundamental-type security analyses, mostly revolved around the user who streamed hours and hours of GameStop-related investing material on his YouTube handle RoaringKitty.

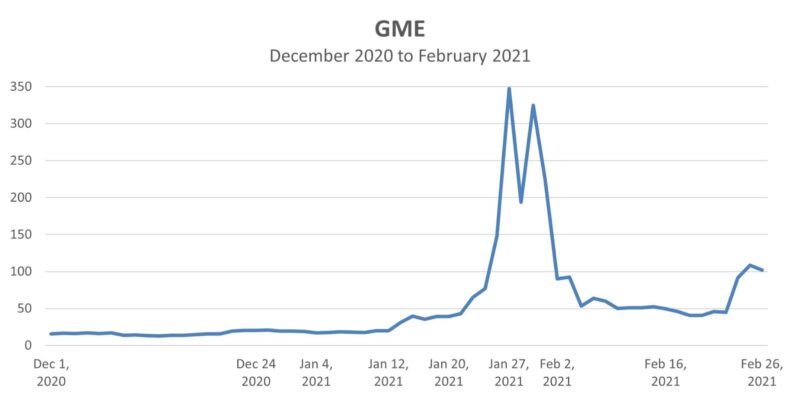

Keith Gill, the man behind RoaringKitty, led a quiet life in a Massachusetts suburb with his family until the GameStop saga exploded. Nobody would have guessed that this seemingly mediocre 35-year-old was about to turn $53,000 into about $50 million – a thousandfold increase in wealth – in just a few months. Streaming countless hours into the Internet’s vastness from the basement of his rented home, he pushed the unending reasons for why GameStop was a value play – deeply undervalued by investors who failed to grasp the turnaround potential. At some point in the winter of 2020-2021, the stars aligned, the WSB forum grew to millions of subscribers, the hip brokerage platform Robinhood brought stock trading to millions of Americans who had never before held an investment – and they all galvanized to put funds behind the buy button for GME. In late-January, this happened:

In most people’s eyes, this was a classic bubble, a mad crowd bidding up the stock of an almost worthless company to stratospheric heights. A few weeks thereafter it came back down again. Retail investors got excited for a minute, Wall Street funds with huge short positions got squeezed – and then the party was over.

At the time, financial journalists and economists were ridiculing any everyday-Joe who traded stocks at all, not to mention the products they didn’t understand, like longs, leverage, options. Next in that vicious blame game was the financial plumbing that allowed Robinhood to offer these products to large swaths of novice investors in the first place, which led to all kinds of criticism of the “regular people” who had the temerity to invest for themselves: They’re wreaking havoc with financial assets; they’re turning investing into a game of YOLO, worthy of a TikTok dance; they’re manipulating the pricing mechanism; and they pose a danger to themselves and to the rest of us.

Those are all true enough, but so is the other side of the story.

Ben Mezrich writes nonfiction in fiction format. In the last decade or so he has successfully covered two of the most important changes to our times – the rise of Facebook and the rise of Bitcoin. In both stories, Mezrich portrayed the David-and-Goliath fights from the point of view of the underdogs – the nerdy coders in what became The Social Network, and the outcast monetary geeks in Bitcoin Billionaires. This time Mezrich moved very fast – from the GameStop saga in January this year, to a finished book in stores eight months later.

Like most Mezrich books, The Antisocial Network: The GameStop Short Squeeze and the Ragtag Group of Amateur Traders That Brought Wall Street to Its Knees is clearly made for the big screen, and it follows a half-dozen characters central to the story. Among them are Gabe Plotkin of Melvin Capital – the Goliath – who together with other Wall Street characters had shorted GameStop stock to the tune of 140 percent of the company’s outstanding float.

Mezrich introduces us to three more down-to-Earth characters: Jeremy, a troubled university kid whose senior year had been all but destroyed by Covid; Kim, a nurse, single mum, and Trump voter who secretly dreams of sticking it to the establishment; and Sara, pregnant and shattered from the dream wedding Covid wouldn’t let her have, working part-time at a pandemic-empty hair salon.

What unites them is their obsession with the WSB board, religiously reading and upvoting comments about GameStop. They adore Gill, and are fascinated by his gainz: a regular nobody, like themselves, could make generation-level money by outwitting Wall Street at its own game — he bet big and turned his financial fortunes around. The personal stories are powerful and give us a fascinating insight into what were probably stories that millions of people identified with last year. All had very little knowledge of financial markets, or in Sara or Jeremy’s case even their own finances. Mezrich has Kim best articulate the appeal of reading WSB and buying GameStop shares:

[r]unning beneath the constant conversation was something Kim recognized: an undercurrent of anger toward the rules that always seemed stacked against regular people like her. […] She loved that she was part of something that felt oddly conspiratorial.

Ines Ferré reported last week for Yahoo Finance:

The GameStop (GME) saga earlier this year gave rise to a movement among retail traders who claim the rules of the markets are rigged against the little guys, favoring the likes of hedge funds and other institutional investors.

Mezrich’s book is part fact, part fiction, but it’s undeniable that he captures something about what happened in those fateful weeks last winter. A few chapters, like the ones focusing on Ken Griffin of Citadel, Emma Jackson of Apex Clearing, or Richard Mashaal of Senvest Management brilliantly gives even a lay reader a fair understanding of what happened behind the scenes – the nuts and bolts behind how financial-market trading works, and who won big and lost bigger.

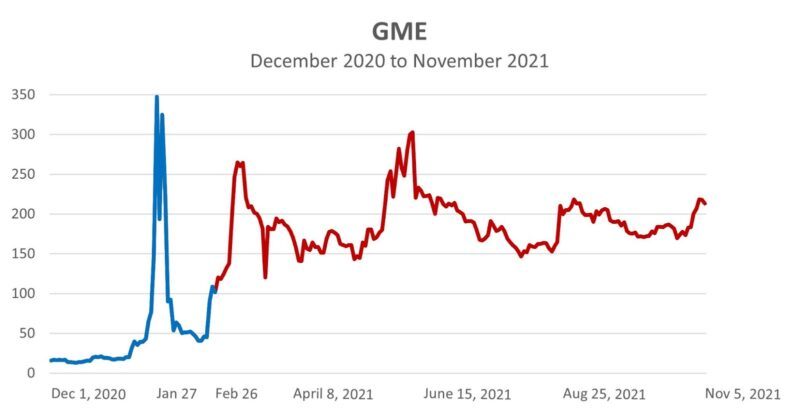

In mid-February, when the stock was back down in the $50 range – still well above where it began the year, or had drowsily traded six months earlier – the stunt looked to be over. By May this year, GME once again hovered around $200, seemingly validating the fundamental analysis at the bottom of the short squeeze debacle. As so often with financial markets, the longer an “obviously odd” phenomenon or “bubble” takes place, the more real it becomes. Either GME is still bubbling and the retail mania is going strong, or at least some of the retail investors saw something that the rest of us didn’t:

Millions were made, billions lost, revenge realized and dreams shattered. The GameStop saga is both disturbing for what it reveals about a society’s divides and the market structure that made it possible.

In principle, financial markets and the assets that trade there are supposed to be society’s best guess at the value of future cash flows – not a plaything by disgruntled plebs. Mezrich’s fast-paced and gripping book is a great tale of what happened on the inside of the most interesting financial phenomenon in recent years.