Classical liberalism – the philosophy of individual liberty and limited government – can often find itself in a deep conundrum. A liberal society maximizes opportunity and gives voice to all – based on ability, work, and merit (economic considerations), rather than birth, gender, or race (non-economic, arbitrary considerations). F.A. Hayek, in The Constitution of Liberty explained that “the mark of a free man is to be dependent for his livelihood not on other peoples’ views of his merit, but solely on what he has to offer them.” It was 1960, so he was still using the customary generic “man” at which contemporary readers might balk; the whole point, of course, was to include women. Voltaire similarly described the leveling effect of markets:

Go into the London Stock Exchange… and you will see representatives of all nations gathered there for the service of mankind. There the Jew, the Mohammedan, and the Christian deal with each other as if they were of the same religion, and give the name of infidel only to those who go bankrupt.

But what can a liberal society do to correct the lingering weight of past illiberal policies? On one hand, individuals who are members of groups that faced past discrimination are often at a disadvantage. On the other, a liberal society cannot, if it is to remain true to its fundamental principles, treat individuals as members of groups, rather than as individuals. Such “reverse discrimination,” which is ultimately just discrimination, lies at the heart of today’s identity politics and has no place in a free society.

Take the example of women, a group that has faced illiberal discrimination in voting rights, property ownership, and more. The literature proposes two paths to advancing gender parity on corporate boards (one measure of economic opportunity for women): quotas, and welfare laws targeted at women (especially state-mandated maternity leave). A dozen countries have laws that guarantee quotas for women on corporate boards and most countries have mandatory maternity leave. The problem with both quotas and welfare, of course, is that they are illiberal. The former treat individuals as members of a class (rather than as individuals), and the latter expands the scope and size of the state.

What if there were a way to advance gender parity, thus advancing the classical liberal goal of giving voice to women, without doing so through a loss of liberty?

As early as 1962, economists Armen Alchian and Reuben Kessel showed that racial discrimination was more prevalent in public utilities than private companies, and more prevalent in regulated private companies than the unregulated. Indeed, discrimination is costly, as employers select workers along non-economic criteria. There is a cost to selecting employees based on preferred non-economic characteristics, rather than ability, and that cost is reflected in diminished revenues for public entities and regulated private businesses, which are shielded from the market discipline of profits.

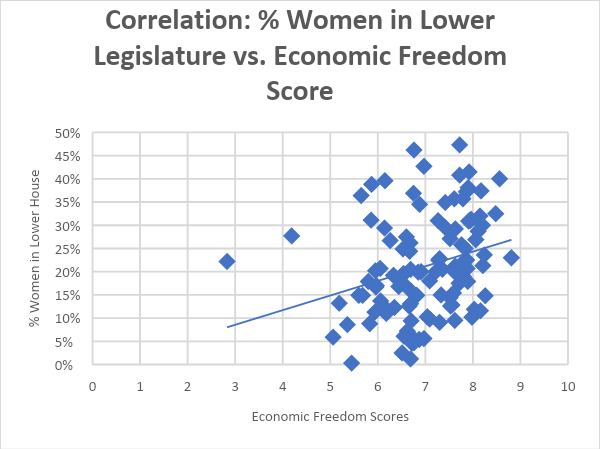

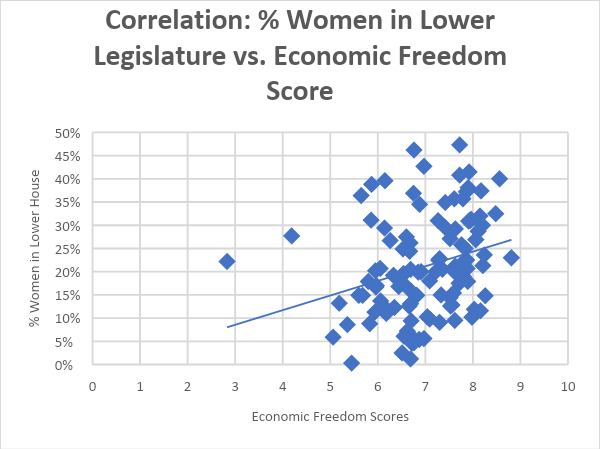

The same applies to the status of women. The literature shows a positive correlation between a country’s economic freedom and the status of women. The mere presence of greater economic freedom – more opportunity for all – improves the status of women.

We dig deeper by looking at the number of women in legislatures and corporate boards in countries that don’t have gender quotas for either, to assess whether economic freedom gives voice to women without the need for legislation. We find that economic freedom is positively correlated with the percentage of women who sit on corporate boards, and the percentage of women in lower houses of the legislature (we focus on lower houses, because the data for bicameral legislatures is too limited).